Historical fiction author Karen A. Chase makes a case for redefining historic monuments as artifacts and letting them stand.

~~~

Relevant History welcomes Karen A. Chase, an author and photographer, and a Daughter of the American Revolution with the Commonwealth Chapter in Virginia. Her first novel, Carrying Independence, is historical fiction about the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Karen will be a Virginia Foundation for the Humanities fellow for the 2019-2020 academic year, with full residency at the Library of Virginia. Originally from Calgary, Alberta, Canada, she is now chasing histories from Richmond, VA. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and Goodreads.

Relevant History welcomes Karen A. Chase, an author and photographer, and a Daughter of the American Revolution with the Commonwealth Chapter in Virginia. Her first novel, Carrying Independence, is historical fiction about the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Karen will be a Virginia Foundation for the Humanities fellow for the 2019-2020 academic year, with full residency at the Library of Virginia. Originally from Calgary, Alberta, Canada, she is now chasing histories from Richmond, VA. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and Goodreads.

Update 22 August 2019: Virginia Humanities has awarded Karen A. Chase a fellowship at the Library of Virginia this fall so she can work on her book project “Eliza! Eliza!: Two 18th-Century Women Who Helped Found and Expand America.” Congratulations, Karen!

*****

Today the populace tore down a statue. When the soldiers heard what their leader had done to his people—his citizens he was supposed to protect—the men lashed ropes to that big lead statue, pulled it to the ground, and hacked it to pieces.

This might have been the news report from this day, 9 July, back in 1776. Soldiers of the Continental Army had gathered in Bowling Green, New York, at the feet of a statue of King George III. It had been erected just six years earlier by a populace grateful that the King had repealed the Townsend Acts. But on this day the Declaration of Independence was read aloud. The list of grievances cited against their King was long—27 points outlining an apathetic and self-appointed despot “unfit to be a ruler of a free people.”

This might have been the news report from this day, 9 July, back in 1776. Soldiers of the Continental Army had gathered in Bowling Green, New York, at the feet of a statue of King George III. It had been erected just six years earlier by a populace grateful that the King had repealed the Townsend Acts. But on this day the Declaration of Independence was read aloud. The list of grievances cited against their King was long—27 points outlining an apathetic and self-appointed despot “unfit to be a ruler of a free people.”

Was it only right that early Americans rallied and destroyed the statue? It was a metaphorical and befitting end to a symbol of injustice, inequality, and entitlement.

I argue that it wasn’t just a monument. It was an artifact. Its destruction was a loss to historians, and moreover a missed opportunity to educate the populace—and us today—by adding context.

Studying art forms expands our understanding of history

Thomas Paine wrote, “The mind once enlightened cannot again become dark.” Studying the art of a time period, much like an era’s architecture or writings, illuminates previous human thought, assumptions, and actions.

This is also what artifacts do. Merriam-Webster defines an artifact as, “something characteristic of or resulting from a particular human institution, period, trend, or individual.”

When the nation abolished slavery, we did not burn Jefferson’s papers that contained notes on his slaves, or raze the slave dwellings at Monticello. Instead, historians and educators examined Jefferson’s writings and the buildings, weighing them against the writings of former slaves and the realities of human suffering resulting from Jefferson’s inability to affect a fully inclusive definition of equality. In so doing, we’ve come to learn about our collective humanity. The horrors and faults. The resilience and enlightenment.

If what has previously been defined as a “monument” is now an “artifact,” by definition we remove it from atop the pedestal and examine it differently. But words are not enough. We also need to visually place newer artifacts alongside them that show context.

The Virginia capitol is leading in the example of adding context

When Mark Warner became governor of Virginia, he was touring the grounds of the Richmond-based capitol with his family. Upon seeing all the statues of the founding fathers of Virginia lining a massive wedding-cake-style monument at the entrance, his daughter, so the story goes, asked him, “Where are all the women?”

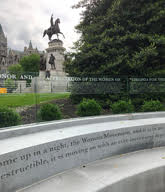

That comment sparked a series of commissions over several years to create new, equally impressive works showcasing Virginia’s historic reality. When children in Richmond walk the grounds now, they’ll still see those founders, but marching toward them, hand raised, is Barbara Rose Johns—Richmond’s Rosa Parks—as part of the Capitol Square Civil Rights Memorial.

After careful study, and input from a broad and inclusive commission, a Native American tribute, “Mantle,” is now nestled into the historic landscape on the southwestern lawn. It is a place for reflection, representative of all Virginia’s nations, and indicative of their history and connection with the natural world.

Currently being developed is also “Voices from the Garden,” the Virginia Women’s Monument. Twelve women from various periods, locations, and ethnicities are being sculpted and cast in bronze to grace an oval space to honor their achievements. Yes, Martha Washington is there, but she’ll sit alongside educator Virginia E. Randolph, and the Pamunkey Chief, Cockacoeske. The bios of all the women are on the website, and the formal dedication will come in October of this year.

Currently being developed is also “Voices from the Garden,” the Virginia Women’s Monument. Twelve women from various periods, locations, and ethnicities are being sculpted and cast in bronze to grace an oval space to honor their achievements. Yes, Martha Washington is there, but she’ll sit alongside educator Virginia E. Randolph, and the Pamunkey Chief, Cockacoeske. The bios of all the women are on the website, and the formal dedication will come in October of this year.

The result of adding context

The result of reconsidering statues as artifacts, and adding context, does more than merely provide funding and projects for modern artists. It educates. An educated populace is a citizenry that grows up to include, contribute, and participate.

Even Thomas Jefferson wrote to Dupont de Nemours in 1816, “Enlighten the people generally, and tyranny and oppressions of body and mind will vanish like evil spirits at the dawn of day.”

For this reason alone, we should not hide or destroy our history. We need artifacts, comparisons, context, and in so doing we shall become better educated. Only then can you, and historians like me, bear witness to a broader narrative and to a truer historical understanding.

Are the sculptures we’re creating for the Virginia capitol grounds enough to heal some of the divisiveness still present about other monuments in our southern city? No. But I think of them much as I regard historical documents like the Declaration of Independence. They are a lovely beginning.

They, like that document drafted in 1776, is a promise to expand our consciousness, to listen to other voices not always our own. It is a promise to strive to be better. And that is far stronger than any monument of bronze or lead.

*****

A big thanks to Karen A. Chase! She’ll give away a paperback copy of Carrying Independence to two readers who contribute comments on my blog. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the United States and Canada.

A big thanks to Karen A. Chase! She’ll give away a paperback copy of Carrying Independence to two readers who contribute comments on my blog. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the United States and Canada.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Beautifully-presented argument in the form of the Jefferson example. May we learn enough history to protect ourselves against the evils of the past when we see them in our own hearts, and to learn from the virtues of the past when we see how far we have to go to embody them.

Cindy, thank you for your remarks. Yes looking back does allow us to see both how far we have come and how far we can go, too. Especially when we tread thoughtfully.

Well said. Thank you for sharing your insight on the importance of preserving our history for future generations.

Like you, Kim, I’d like to know our children’s children will see how we learned and grew so they can, too.

This has been my contention. Tearing down the past does not fix what was done decades ago.

Very nicely said.

What, to me, seems to have been lost is the realization that only incremental steps could be achieved. Witness the French Revolution that devolved into terror, to the regret of an agonized Lafayette.

Kevin and Liz, exactly. Our insights today do not undo what has come before. But rash decisions, can add further damage to an already inflicted wound. The beauty of the commissions that are making the women’s monument and the Indian tribute here in Virginia, are about thoughtful exchanges that result in consensus. They are about inclusion. That is a step in the right direction when it comes to learning from our history.

You explain this concept so beautifully! Should be required reading for not only schools, but politicians!

Oh, Norma, what a nice comment. Reason should be our guide here, not politics. Thank you!

Hopefully, we learn from the past and tearing down monuments doesn’t further our need to understand the past. Erase history and mistakes may be made again. Learn, adjust and try to understand the things that made America what it is, both the good and the bad. History is history. Don’t let anyone take it away, even if it’s in the form of a monument.

Karen, thank you for this well-thought out post. I am very glad to hear what the state of Virginia is doing to address the topic, and hope that other states follow in their footsteps. I also look forward to reading your book, whether or not I win the drawing.

Jane & Judy, Thank you and I am beyond pleased that looking at these objects as an opportunity to education is so well received and shared. And I hope you enjoy the book, too, regardless of who is selected to receive the copy.

Karen,thank you for these thoughts. It certainly would be nice if we could educate the people who are wanting to destroy our history that these “monuments, artifacts” help us tell the history or our country and we all learn from our history. What an excellent way to teach history other than in a text book. Please keep trying to spread the word.