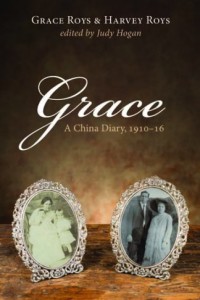

Relevant History welcomes Judy Hogan, who founded Carolina Wren Press and has been active in North Carolina over forty years as publisher, teacher, and writing consultant. In April 2017 Grace: A China Diary, 1910-16, which she edited and annotated, was released by Wipf and Stock, and Political Peaches came out 1 June 2017. Six other mystery novels, are in print. Two volumes of poetry came out in 2013 and 2014: Beaver Soul and This River: An Epic Love Poem. Her papers and diaries are in the Sallie Bingham Center, Duke University. She has taught creative writing since 1974. She lives and farms in Moncure, N.C. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site and blog, and follow her on Goodreads.

Relevant History welcomes Judy Hogan, who founded Carolina Wren Press and has been active in North Carolina over forty years as publisher, teacher, and writing consultant. In April 2017 Grace: A China Diary, 1910-16, which she edited and annotated, was released by Wipf and Stock, and Political Peaches came out 1 June 2017. Six other mystery novels, are in print. Two volumes of poetry came out in 2013 and 2014: Beaver Soul and This River: An Epic Love Poem. Her papers and diaries are in the Sallie Bingham Center, Duke University. She has taught creative writing since 1974. She lives and farms in Moncure, N.C. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site and blog, and follow her on Goodreads.

*****

Until I read my grandmother Grace Roys’s diary kept in China, I thought missionaries were always serious and staid. In 2004 I decided to annotate and publish it. They were not staid. My grandfather Harvey, who went to China in 1910, sponsored by the YMCA to teach physics at Kiang Nan government college, got into pillow fights. Grace who was teaching at a Methodist School for Chinese girls, enjoyed riding horses and chasing wild pigs. He met her shortly after he arrived. They belonged to a close-knit community of American Protestant missionaries. The young people met often to play tennis, swim, sing around the piano, or play dominoes.

As the weather got hot—the climate being like South Carolina—the missionary families went to Kuling, a mountain resort for missionaries. There were lovely places to picnic, swim, and, in the evenings, read a book aloud. A Girl of the Limberlost was a favorite. The heroine had a difficult mother, but she became able to support herself by catching rare moths for a collector. Harvey caught a few moths himself. He went every morning to the swimming pool for a “dunk” and helped clean the pool.

Harvey and Grace fall in love

In the summer of 1910, they came to an “understanding” that they would marry. Unfortunately, Grace’s father thought Harvey wasn’t good enough. This made Grace very sad. She had a nervous breakdown and had to go to a mission hospital in Soochow. Then they let her marry Harvey in December 1910. The doctors and the parents were quite worried, but Harvey could never abandon his “little lady” and risked the marriage on 19 December 1910. He writes on 23 December, “Grace’s birthday. Grace is 21—of age but ‘not her own boss,’ as she says. I think she is boss of two.” A year later he writes on 23 December: “Grace is 22 and happy…No days like these.”

In the summer of 1910, they came to an “understanding” that they would marry. Unfortunately, Grace’s father thought Harvey wasn’t good enough. This made Grace very sad. She had a nervous breakdown and had to go to a mission hospital in Soochow. Then they let her marry Harvey in December 1910. The doctors and the parents were quite worried, but Harvey could never abandon his “little lady” and risked the marriage on 19 December 1910. He writes on 23 December, “Grace’s birthday. Grace is 21—of age but ‘not her own boss,’ as she says. I think she is boss of two.” A year later he writes on 23 December: “Grace is 22 and happy…No days like these.”

By December 1911, they had lived through the Sun Yat-sen Revolution, the first successful revolution in China, which caused the downfall of the Manchu emperors. The last big battle took place near Nanking. The American consul ordered all women and children to come to the consulate or evacuate on 8 November. Grace decided to go to Shanghai where her parents lived. On 14 November, Harvey went to Shanghai, too. My mother was conceived during this revolution. When Grace and Harvey returned, they learned that three hundred soldiers had camped in his college building, but his physics lab was safe. Grace, fluent in Chinese, helped him speak to those in charge, and Harvey went back to teaching.

My mother is born in Kuling

On 17 July 1912, Grace gave birth to Margaret Elizabeth Roys. Her baby adventures are told. She was toilet trained early, and one year later went from Monday, 5 p.m. to Tuesday, 4 p.m. without wetting her diaper. Later she learned to request the pot, but Grace wanted her to say: “Hi, hi.” not “Want er sit on er pot.” Baby Richard (Dick) came 5 October 1913. On 14 November Harvey writes: “Bath tub with Richard in it fell off the board into the big tub. Richard was ducked in cold water but did not receive any apparent injuries.” Margaret had mixed feelings about baby brother. Grace found her pounding on Richard with her fist. saying, “Bore hole dere.”

On 17 July 1912, Grace gave birth to Margaret Elizabeth Roys. Her baby adventures are told. She was toilet trained early, and one year later went from Monday, 5 p.m. to Tuesday, 4 p.m. without wetting her diaper. Later she learned to request the pot, but Grace wanted her to say: “Hi, hi.” not “Want er sit on er pot.” Baby Richard (Dick) came 5 October 1913. On 14 November Harvey writes: “Bath tub with Richard in it fell off the board into the big tub. Richard was ducked in cold water but did not receive any apparent injuries.” Margaret had mixed feelings about baby brother. Grace found her pounding on Richard with her fist. saying, “Bore hole dere.”

I also inherited two yearbooks of the Hillcrest School the missionary mothers began, and which Margaret and Dick attended. The mothers with small children worked together to teach the primary grades. Eventually they taught high school, too. Hillcrest emphasized science and had a Watch Guard branch of the Agassiz Society organized in Nanking in October 1895. They encouraged their members to “watch and guard—thus studying mother nature.” Its motto, was “Little by little the bird builds its nest and the child learns.” They sponsored debates, e.g., in December 1903: “Resolved, that we learn more from observation than by books.” The founder of the society was Alexander Agassiz, 1835–1910, a U.S. zoologist. He emphasized careful observation. Grace’s maternal grandfather, James Woodrow, studied at Harvard with Agassiz.

I also inherited two yearbooks of the Hillcrest School the missionary mothers began, and which Margaret and Dick attended. The mothers with small children worked together to teach the primary grades. Eventually they taught high school, too. Hillcrest emphasized science and had a Watch Guard branch of the Agassiz Society organized in Nanking in October 1895. They encouraged their members to “watch and guard—thus studying mother nature.” Its motto, was “Little by little the bird builds its nest and the child learns.” They sponsored debates, e.g., in December 1903: “Resolved, that we learn more from observation than by books.” The founder of the society was Alexander Agassiz, 1835–1910, a U.S. zoologist. He emphasized careful observation. Grace’s maternal grandfather, James Woodrow, studied at Harvard with Agassiz.

In the 1920 yearbook, Hillcrest student Julia Wilson describes the trip to Kuling. They traveled first by boat up the Yangtze River, later by carriage, then by sedan chair up the mountain.

Among the many things which we saw on our way, the most common…was the many house boats. Some of them had families of beggars on them, others had people who were a good deal better off, some were larger, some smaller, some with sails on, some without them, all sailing up and down the river in a way that seemed aimless…All along the banks of the river and inland for miles around, we could see the rice fields with little villages dotted here and there, each with their groups of dogs and children…On the bank of the river so near you could almost say on the river were numerous little huts barely high enough for a man to stand in. These were often surrounded by miles of very tall reed grass which the Chinese burn instead of wood or coal…When we were nearing towns, large or small, we would meet a man in a sampan, with a long stick driving a very large group of ducks which seemed too many for one man to drive…This was the way in which he drives his pigs to market, only they…were ducks…As we drew near to Kiukiang we saw…several ranges of mountains in the distance looking more like mirage than a range of mountains and the ones that we were traveling to in order to get away from the heat of the plains.

*****

A big thanks to Judy Hogan. She’ll give away a paperback copy of Grace: A China Diary, 1910-16 to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Judy Hogan. She’ll give away a paperback copy of Grace: A China Diary, 1910-16 to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.