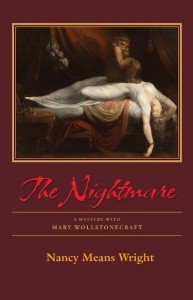

Relevant History welcomes back historical novelist Nancy Means Wright, who has published fourteen novels with St Martin’s Press, Dutton, Perseverance Press, and elsewhere, including two historical mysteries featuring 18th-century Mary Wollstonecraft. Her most recent historicals are Walking into the Wild for tweens, and the multi-generational novel, Queens Never Make Bargains. Her short stories, both mystery and mainstream, appear in American Literary Review, Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Level Best Books, et al. Her children’s mysteries have received an Agatha Award and Agatha nomination. Nancy lives in Middlebury, Vermont, with her spouse and two Maine Coon cats. For more information, check her web site, and look for her on Facebook.

Relevant History welcomes back historical novelist Nancy Means Wright, who has published fourteen novels with St Martin’s Press, Dutton, Perseverance Press, and elsewhere, including two historical mysteries featuring 18th-century Mary Wollstonecraft. Her most recent historicals are Walking into the Wild for tweens, and the multi-generational novel, Queens Never Make Bargains. Her short stories, both mystery and mainstream, appear in American Literary Review, Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Level Best Books, et al. Her children’s mysteries have received an Agatha Award and Agatha nomination. Nancy lives in Middlebury, Vermont, with her spouse and two Maine Coon cats. For more information, check her web site, and look for her on Facebook.

*****

Some people move ahead with the times—I’ve been stepping behind. After a decade with a contemporary farmer sleuth, I journeyed back into the 18th-century and into the head and heart of real life feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. I relived Mary’s turbulent adventures as governess in an Irish castle and as author of the groundbreaking Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)—for which they called her a “philosophical wanton.” And I wrote a middle grade novel, Walking into the Wild, set in the 18th-century Republic of Vermont, in which three young siblings walk up into a wilderness filled with catamounts and Tories, in search of a captured father.

Now I’ve reached a stage in my life where I want to dig into my own family roots. In Queens Never Make Bargains, I tell the story of my Scottish grandmother, who as a young woman, alone, took ship aboard the Campania, a turn-screw, steel structure with a veranda café for first class (my granny rode third class) from Port Glasgow in Scotland to New York City. Her half-sister had died in childbirth and she was to be nanny to her uncle’s brood of seven children. She later married him and had six more—thirteen in all. But it wasn’t until the 1980s that I discovered in the Edinburgh, Scotland archives that my grandmother was illegitimate! It took a glass or two of Scotch for me to digest this stunning news—and then I wrote a novelette for Seventeen Magazine that ultimately turned into a full-blown novel.

Castle in the Highlands

Of course I wasn’t alive when my grandmother took that ship. I have only basic facts, along with family stories sifted down through the years, and myriad visits to Leven Fifeshire where my mother’s family lived in Scotland near the Firth of Forth, and where archeologists had dug up the body of a Viking in full armor. And I placed scenes near the Menzies Castle in highland Weem where my father’s forebears lived. My daughter and a friend once sneaked into the elegant ballroom after the castle was locked and had a fitful night’s sleep filled with dreams of kilts and daggers!

Of course I wasn’t alive when my grandmother took that ship. I have only basic facts, along with family stories sifted down through the years, and myriad visits to Leven Fifeshire where my mother’s family lived in Scotland near the Firth of Forth, and where archeologists had dug up the body of a Viking in full armor. And I placed scenes near the Menzies Castle in highland Weem where my father’s forebears lived. My daughter and a friend once sneaked into the elegant ballroom after the castle was locked and had a fitful night’s sleep filled with dreams of kilts and daggers!

The area is magnificent. The whole valley spins at the feet of the castle: braes, burns, the old houses and trees of Weem and Aberfeldy, Dull and Fortingall. This had been Menzies country since the thirteenth century when the laird was granted the lands and became in loco paternis to the people, renting them land, I was told, in return for certain favors. It was those favors, my father claimed, that spawned our branch of the family!

Life, Love, and Art in Cherry Valley, Vermont

After reaching America, my fictional Scots nanny, Jessie, moves with her uncle and his unruly brood to a town I call Cherry Valley, Vermont. The latter is based on the Vermont machine tool town of Springfield, which was allegedly on Hitler’s World War II “hit list” for bombing. Russian and Poland immigrants flocked there during and after WWI, and I’ve created a love affair between Jessie, who teaches English to the foreigners, and a young Polish poet. Her uncle, of course, does everything he can to separate the lovers.

So far as I know, my grandmother was never in love with a young Pole, who despite his pacifism, fights for his new country in WWI, but like my mother who never told about her illegitimate origins (if indeed she knew), my grandmother stored her secrets deep inside.

One of my characters is based on Joe Henry, a real life artist from Springfield, Vermont (1912-1973), whose paintings I’d seen in an art gallery. I was amazed at the quality of his work, for polio had left him with no use of his opposable thumbs. To paint, he would stand propped in braces before a cardboard table, and then sweep a painting onto canvas or the back of newspaper—for Joe had little money for art materials. I interviewed a compassionate veterinarian who took him on his farm rounds in the 1930s, and gave him subject matter for his work, which eventually found its way to N.Y.C. galleries. One of his paintings graces the cover of my book.

Banned Plays and War Planes

Since the novel tells the fictionalized story of three passionate Menzies women who carry on their lives through two world wars, a pandemic, and a Great Depression, I write from three different points of view. In Part 3, I’m in the head of Victoria, the youngest of Jessie’s charges, who grows into a rebellious young woman in love with the 30’s theater (a theater killed by fanatical congressmen), with her (married) Vassar College professor, and with the Spitfire airplane.

After seeing Colonel Charles Lindbergh set down his famous Spirit of St. Louis in a nearby field (he truly did in 1927), she learns to fly, and ferries planes in wartime London. Women pilots are not allowed to carry guns, although like Victoria, they do encounter Messerschmitts in the embattled air. My older brother, a pilot and navigator, steered me through the mysteries of Victoria’s beloved Spitfire, with its snug single seat and overhead “bubble” which she calls “the dome of heaven—like flying out of the self.” Like the WWII female pilots I’ve researched, she has her share of misadventures—including a landing in foul weather in which a fellow pilot just ahead of her drowns in his plane.

After seeing Colonel Charles Lindbergh set down his famous Spirit of St. Louis in a nearby field (he truly did in 1927), she learns to fly, and ferries planes in wartime London. Women pilots are not allowed to carry guns, although like Victoria, they do encounter Messerschmitts in the embattled air. My older brother, a pilot and navigator, steered me through the mysteries of Victoria’s beloved Spitfire, with its snug single seat and overhead “bubble” which she calls “the dome of heaven—like flying out of the self.” Like the WWII female pilots I’ve researched, she has her share of misadventures—including a landing in foul weather in which a fellow pilot just ahead of her drowns in his plane.

So the narrative moves in and out of time (1912-1945). I’ve been researching it off and on for years, exploring the roles of immigrants and their conflicting cultures and religions. I’ve been particularly interested to see how external events shape and alter our lives, and how, like many of my ancestors—and yours as well, no doubt—we cope with and survive them, even when we lose what we most love.

*****

A big thanks to Nancy Means Wright. She’ll give away copies of Queens Never Make Bargains (ebook or paperback) to three people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available within the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom.

A big thanks to Nancy Means Wright. She’ll give away copies of Queens Never Make Bargains (ebook or paperback) to three people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available within the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.