Historical mystery author Libi Astaire describes how entrepreneur Sake Deen Mahomed took Regency England by storm with his exotic, Indian-ambiance vapor bathhouse.

###

Relevant History welcomes back Libi Astaire, author of the award-winning Jewish Regency Mystery Series in which a wealthy widower, Mr. Ezra Melamed, turns sleuth to solve a series of crimes affecting Regency London’s Jewish community. In addition to her historical mystery series, Libi is the author of The Latke in the Library: Other Mystery Stories for Chanukah, a Chanukah-themed modern-day spoof of Agatha Christie mystery novels. To learn more about Libi and her books, visit her web site and follow her on Facebook.

Relevant History welcomes back Libi Astaire, author of the award-winning Jewish Regency Mystery Series in which a wealthy widower, Mr. Ezra Melamed, turns sleuth to solve a series of crimes affecting Regency London’s Jewish community. In addition to her historical mystery series, Libi is the author of The Latke in the Library: Other Mystery Stories for Chanukah, a Chanukah-themed modern-day spoof of Agatha Christie mystery novels. To learn more about Libi and her books, visit her web site and follow her on Facebook.

*****

The words “Regency England” often conjure up an image of demure Austenesque young ladies dressed in muslin gowns, eyeing eligible young gentlemen across the dance floor. But the era had its share of colorful characters, too—and it was more diverse than people might suppose. My Jewish Regency Mystery series, for example, revolves around London’s thriving Jewish community. Another example can be found in the fourth volume of the series, The Vanisher Variations, where one of the characters, Sake Deen Mahomed, is from India.

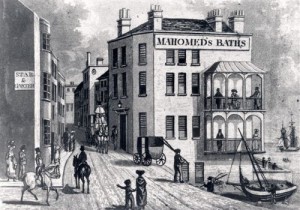

Sake Deen was a real person. His rise to fame, if not fortune, followed a pattern typical of many outsiders who wished to partake of the many pleasures that 19th-century England had to offer. In the early 1800s, he opened an authentic Indian “vapour bathhouse” in Brighton, a watering hole that had become fashionable thanks to the Prince Regent. The future King George IV was so enamored of these vapor baths that he had one installed at the opulent residence he was building, the Brighton Pavilion. With the Prince Regent as a patron, Sake Deen’s success was assured.

Sake Deen was a real person. His rise to fame, if not fortune, followed a pattern typical of many outsiders who wished to partake of the many pleasures that 19th-century England had to offer. In the early 1800s, he opened an authentic Indian “vapour bathhouse” in Brighton, a watering hole that had become fashionable thanks to the Prince Regent. The future King George IV was so enamored of these vapor baths that he had one installed at the opulent residence he was building, the Brighton Pavilion. With the Prince Regent as a patron, Sake Deen’s success was assured.

“A cure to many diseases”

Mahomed first arrived in England in the late 1700s. Orphaned when young, he learned to be a surgeon while serving in the East India Company’s army. There he found a patron in the British army officer Captain Godfrey Evan Baker; when Baker returned to England, Sake Deen went with him.

During a brief stay in Ireland, he fell in love with a young Irish woman named Jane Daley. Jane’s parents opposed the marriage. So did the Anglican Church; marriages between Protestants and non-Protestants were illegal. To satisfy the church, Mahomed, a Muslim, converted. The Daley family was harder to appease, so the young couple eloped.

Mahomed’s initial business venture was the Hindoostane Coffee House, the first Indian restaurant in England. The food was praised, but the restaurant wasn’t profitable. The Mahomeds therefore moved to Brighton, where they opened a commercial bathhouse.

In addition to offering steam baths fragranced with exotic oils from India, one of Mahomed’s specialties was giving his clients a “shampoo,” which in those days meant a massage. In typical Regency medical style, he boasted that his shampoos were “a cure to many diseases”—rheumatism, gout, and even lame legs, among other ailments. Part of the establishment’s décor was a display of discarded crutches; their former owners had given them to Sake Deen as a gift, after they were cured and no longer needed them.

In addition to offering steam baths fragranced with exotic oils from India, one of Mahomed’s specialties was giving his clients a “shampoo,” which in those days meant a massage. In typical Regency medical style, he boasted that his shampoos were “a cure to many diseases”—rheumatism, gout, and even lame legs, among other ailments. Part of the establishment’s décor was a display of discarded crutches; their former owners had given them to Sake Deen as a gift, after they were cured and no longer needed them.

The vapor bathhouse was a great success. Soon, the wealthy and influential were flocking to the seaside resort to visit “Dr. Brighton, the Shampooing Surgeon,” as Mahomed was called, to take one of his famous shampooing cures.

Jewel in the crown

Although he had converted to Christianity and settled in England, Mahomed took pride in Indian culture and his role in introducing it to the British. He was lucky in that interest in all things Indian was on the rise, thanks to the expansion of the British Empire. The Brighton Pavilion, whose final design was heavily influenced by Indian architecture, was perhaps the most striking example of the craze.

He was also lucky that he had a flair for business and marketing—a skill that many of his fellow Indians living in England lacked. Indian women often came to England as house servants; when they were dismissed without pay from their position, they had few skills and nowhere to go. The men were often lascars, Indian sailors, escaping from the hardships of serving under cruel masters and a life at sea. They too found it hard to adjust and quickly fell into poverty.

Mahomed, though, came from the educated class and so he had an advantage; although unlike the British upper class he had no qualms about promoting himself. He savvily made sure his bathhouse was exotic enough to suggest the East, while respectable enough to appeal to a British dowager duchess. That’s why Lady Lennox, the rich noblewoman in The Vanisher Variations who disappears while taking a vapor bath, could visit the bathhouse without raising eyebrows. While Sake Deen took care of the male visitors, his wife Jane oversaw the shampooing of the women.

But by the end of the 1830s, Mahomed’s star was fading. As the flamboyant Regency years transitioned into the staider Victorian era that was to follow, some objected to his overly enthusiastic marketing tactics. Others whispered that he had committed the gravest sin of all; his bathhouse was woefully outdated and boring.

When he passed away in 1851, having reached his ninth decade, few noticed. But for those interested in Regency England, Sake Deen Mahomed remains a prime example of the unexpected diversity that existed during this always entertaining era.

*****

A big thanks to Libi Astaire! She’ll give away a Kindle ebook copy of The Vanisher Variations to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Libi Astaire! She’ll give away a Kindle ebook copy of The Vanisher Variations to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter. And look for my Patreon, coming soon!