Relevant History welcomes back Mary Reed, who, with Eric Mayer, co-authors the John, Lord Chamberlain, Byzantine mystery series and, writing under the transparent nom de plume Eric Reed, the Grace Baxter mysteries, set in WWII England. An Empire for Ravens, John’s latest adventures, will be published by Poisoned Pen Press in October 2018. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, blog, and author page, and follow her on Twitter.

*****

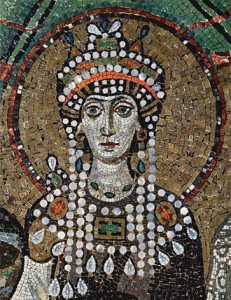

The depiction of Empress Theodora in our John, Lord Chamberlain mysteries is based on her character as described in contemporary historian Procopius’ Secret History.

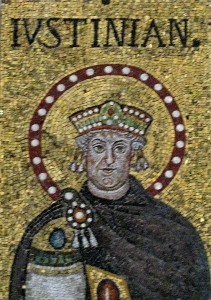

Justinian I ruled the Byzantine Empire from 527 to 565, and once married to him, Theodora was in effect co-ruler and thus in a position help the downtrodden in various ways—and women in particular.

According to late legend she was spinning wool and living a virtuous life when Justinian, heir to the throne via his uncle Emperor Justin I, fell in love with her. We might well speculate how likely it was their paths would cross given their disparate social positions and especially her colourful past.

A notorious act

Theodora had been an actress, regarded as synonymous with prostitution. Procopius mentions her notorious semi-naked act presenting the story of Leda and the Swan, in which trained fowl pecked grain from her groin. Even before that, according to his Secret History, when prepubescent she worked in a brothel servicing customers while “still too young to know the normal relation of man with maid, but consented to the unnatural violence of villainous slaves…” Common gossip had it Theodora worked her way back to Constantinople by prostitution after being cast off by a man named Hecebolus, whom she had accompanied abroad when he became governor of Pentapolis in North Africa.

Theodora had been an actress, regarded as synonymous with prostitution. Procopius mentions her notorious semi-naked act presenting the story of Leda and the Swan, in which trained fowl pecked grain from her groin. Even before that, according to his Secret History, when prepubescent she worked in a brothel servicing customers while “still too young to know the normal relation of man with maid, but consented to the unnatural violence of villainous slaves…” Common gossip had it Theodora worked her way back to Constantinople by prostitution after being cast off by a man named Hecebolus, whom she had accompanied abroad when he became governor of Pentapolis in North Africa.

Procopius is a venomous writer, but there appears to be some truth in his allegations. John of Ephesus was a Monophysite bishop and therefore adhered to the belief Christ had but one nature, a theological distinction causing significant upheaval in the church for years. He would surely would be grateful to Theodora, who provided refuge for a number of his fellow co-religionists, going so far as to hide them in Constantinople’s Hormisdas Palace and extracting a promise from Justinian he would protect them after her death. Nevertheless, John mentions in his Ecclesiastical History that Theodora had a daughter before her marriage, and in his Lives of the Eastern Saints refers to her in an offhand manner as “Theodora who came from the brothel.”

A stumbling block overcome

But love is blind and Justinian wished to marry her. The major stumbling block was it was illegal for an actress and a man of Justinian’s rank to marry. The law had to be changed to get around the difficulty, but the problem was Euphemia, Justin’s wife, was set against such a marriage. She herself had been a slave, purchased by Justin well before he ever had any notion he would rise to be emperor. As empress Euphemia staunchly upheld imperial dignity, and it was not until she was dead that the needed legislation could be passed.

It laid down “…women who had devoted themselves to theatrical performances, and, afterwards having become disgusted with this degraded status, abandoned their infamous occupation and obtained better repute, should have no hope of obtaining any benefit from the Emperor, who had the power to place them in the condition in which they could have remained, if they had never been guilty of dishonorable acts, We, by the present most merciful law, grant them this Imperial benefit under the condition that where, having deserted their evil and disgraceful condition, they embrace a more proper life, and conduct themselves honorably, they shall be permitted to petition Us to grant them Our Divine permission to contract legal marriage when they are unquestionably worthy of it.”

Marriage brings power

Justinian and Theodora were therefore able to marry. As empress Theodora is regarded as having a hand in legislation helping those forced into prostitution, some of them only children or country girls sold by their impoverished parents or lured to the city with fine promises of a better life. It is not unlikely this was so, given both her past and Justinian’s statement that “Having reflected upon all these matters, and discussed them with Our Most August Consort whom God has given Us…We enact the present law,” in this case one forbidding the purchase of office.

Justinian’s law against pandering declared “No one shall carry on the trade of pandering, prostitute women in his house or in public for gratification of the passions, or do any other act to that end.” It commanded guilty parties to leave Constantinople, providing that “if any one hereafter takes a girl against her will and keeps her force in order to make money for himself by meretricious traffic, shall be arrested by the worshipful praetors of this fortunate city and visited with the extremest penalty.”

Help for the downtrodden

Theodora made other efforts to help these unfortunate women. An imperial building on the Asian side of the Bosphorus became a refuge known as Metanoia (repentance), and about five hundred former prostitutes were sent there. Procopius waspishly declares residency was not a matter of choice for these women, and some committed suicide by throwing themselves from a height, but he does not deny Theodora’s role in the matter.

Theodora was involved in other good works such as founding hospices and an orphanage, repairing holy buildings, charitable giving, and so on. These acts are acknowledged by an inscription in the Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus in Istanbul, referring to her as “God-crowned Theodora whose mind is bright with piety, whose toil ever is unsparing efforts to nourish the destitute.” Justinian was just as active in attempts to better the life of his subjects, including judicial reforms and an extensive building programme covering public works, defences, and numerous churches, most notably the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. It is worth noting the imperial couple are regarded as saints by the Eastern Orthodox Church.

It appears Theodora’s marriage to Justinian was a true love match. Even Procopius in his History of the Wars admits this to be the case, referring to Justinian’s “extraordinary love” for her. It seems to be the truth, for Justinian did not remarry after Theodora died in 548, although he survived her by seventeen years.

*****

A big thanks to Mary Reed. She’ll give away an electronic copy (ePub format) of An Empire for Ravens to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Mary Reed. She’ll give away an electronic copy (ePub format) of An Empire for Ravens to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.