Relevant History welcomes Judith Starkson, who writes historical fiction and mysteries set in Troy and the Hittite Empire. Her debut, Hand of Fire, set within the Trojan War, combines history and legend in the untold story of Achilles’ captive Briseis. Hand of Fire was a semi-finalist in the prestigious M.M. Bennett’s Award for Historical Fiction. Starkston’s upcoming mystery series features Queen Puduhepa of the Hittites and won the San Diego State University Conference Choice Award. Puduhepa signed the first surviving peace treaty in history with Pharaoh Ramesses II; now she’s a sleuth. Ms. Starkston is a classicist (B.A. UC, Santa Cruz, M.A. Cornell). For more information, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

Relevant History welcomes Judith Starkson, who writes historical fiction and mysteries set in Troy and the Hittite Empire. Her debut, Hand of Fire, set within the Trojan War, combines history and legend in the untold story of Achilles’ captive Briseis. Hand of Fire was a semi-finalist in the prestigious M.M. Bennett’s Award for Historical Fiction. Starkston’s upcoming mystery series features Queen Puduhepa of the Hittites and won the San Diego State University Conference Choice Award. Puduhepa signed the first surviving peace treaty in history with Pharaoh Ramesses II; now she’s a sleuth. Ms. Starkston is a classicist (B.A. UC, Santa Cruz, M.A. Cornell). For more information, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

*****

Getting to the truth in wartime has always been challenging. Governments save face and misrepresent their military strength and their moral rectitude as combatants. As a child, I remember the photographs of the My Lai massacre in Vietnam undermining my own sense of my government’s position in that unfortunate war.

Ancient propaganda in stone

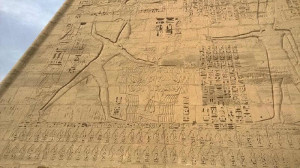

[Ramesses smiting the Hittites, Ramesseum, Photo by Morgana] In Egypt following the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE, Pharaoh Ramesses ordered a version of this battle carved onto walls of his Ramesseum, his memorial temple to himself (as well as some other buildings—repetition was a virtue in his propaganda efforts). The Pharaoh, giant-sized, is shown crushing the very tiny Hittites single-handedly with his scepter. You would assume from this grand and heroic scene that Ramesses had retaken all the disputed lands in Syria from the Hittites, that he was the undisputed victor. Pharaohs get to tell history their way in their own land. Who’s going to argue with a god who rules the land with absolute authority? (More or less, putting aside those pesky uppity priests and internecine family squabbles, etc.)

[Ramesses smiting the Hittites, Ramesseum, Photo by Morgana] In Egypt following the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE, Pharaoh Ramesses ordered a version of this battle carved onto walls of his Ramesseum, his memorial temple to himself (as well as some other buildings—repetition was a virtue in his propaganda efforts). The Pharaoh, giant-sized, is shown crushing the very tiny Hittites single-handedly with his scepter. You would assume from this grand and heroic scene that Ramesses had retaken all the disputed lands in Syria from the Hittites, that he was the undisputed victor. Pharaohs get to tell history their way in their own land. Who’s going to argue with a god who rules the land with absolute authority? (More or less, putting aside those pesky uppity priests and internecine family squabbles, etc.)

Reality on the Hittite side

However, the Hittites, Ramesses’ foes, were no weaklings, even if they didn’t leave a pictorial version of their own of this key battle. A close look at the aftermath of Kadesh shows that Ramesses engaged in some unjustified propaganda.

First of all, you may be wondering who the Hittites were. Ramesses, of “let my people go” Moses fame (if we can stray from history into possibly legendary material), is a relatively familiar character from the dust pile of history. But there’s a good chance you haven’t heard of Great King Muwattalli and his younger brother and most reliable general, Hattusili. The Hittite Empire sprawled from the western Aegean coast of what is now Turkey across the Anatolian plateau and down into what is now Syria and Lebanon. The Hittite Great King and the Egyptian Pharaoh addressed each other as “Brother” in recognition of their equal power. Sometimes a Babylonian or Syrian king got to claim such lofty status, but not always. So the fact that the Egyptian kingdom stretched up into the Levant and the Hittite Empire stretched down into the Levant, and thus they butted up against each other was just sure to cause trouble.

Ramesses, early in his reign, was determined to match the heroic achievements of his predecessors after a generation or two of less than heroic pharaohs dimming the glory of Egypt’s martial reputation. He made a series of raids into these disputed areas in 1275 and then launched a full-scale war in 1274. Muwattalli was ready for him. More ready than the inexperienced Ramesses, as it turns out.

The battle

In his eagerness to take back his Syrian territory, Ramesses launched ever northward, ahead of his main fighting divisions. Not far from Kadesh, he found two Bedouins who claimed to want to leave the service of the Hittite Great King and join the Egyptians. They explained that Muwattalli’s army was far away in the Land of Aleppo. Ramesses took them at their word, sent no scouts out, and crossed the river (thus separating himself even more from his troops who hadn’t made it there yet) to set up camp outside Kadesh.

Actually, the Hittite main force was camped on the far side of Kadesh. They made a secret attack and nearly wiped out the whole Egyptian army. The eminent historian Trevor Bryce describes what happened next: “Ramesses, making up for his earlier recklessness and gullibility, stood his ground with an exemplary show of courage and leadership—at least according to his own version of the events” (The Kingdom of the Hittites p. 237).

How much this turn of the battle was due to Ramesses’ personal leadership skills in battle and how much was due to the timely arrival of some Egyptian reinforcements will forever remain debatable. But what we do know is that Ramesses listed the slain Hittite officers on the walls of the Ramesseum, and we have no reason to doubt the accuracy of that part—the Hittites took huge losses. We also know that the Hittites avoided renewed conflict, which again shows the losses they must have suffered in men and weaponry.

The long-term result: peace

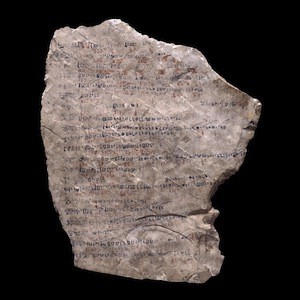

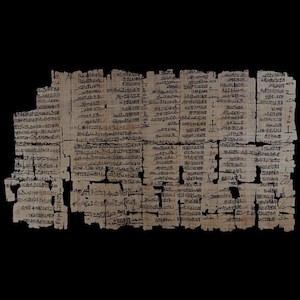

[Treaty of Kadesh between Ramesses and Hattusili/Puduhepa]It was a war whose large scale had done permanent damage to both sides, and these two sides eventually signed the first extant peace treaty in history, which you can see in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum. By that time, younger brother Hattusili was Great King and his indomitable wife, Puduhepa, also placed her seal on this treaty. Queens got a lot of respect among the Hittites, not at all like most of their ancient contemporaries.

[Treaty of Kadesh between Ramesses and Hattusili/Puduhepa]It was a war whose large scale had done permanent damage to both sides, and these two sides eventually signed the first extant peace treaty in history, which you can see in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum. By that time, younger brother Hattusili was Great King and his indomitable wife, Puduhepa, also placed her seal on this treaty. Queens got a lot of respect among the Hittites, not at all like most of their ancient contemporaries.

The key to understanding who “won” Kadesh lies in the spoils. The Hittites regained control of some cities that had recently fallen into Egyptian influence and they took control of several cities that had always been in the Egyptian camp. Does not sound like an Egyptian win. The eventual treaty does not spell out the boundaries in detail, but it leaves in place the status quo after Kadesh—noticeably in Hittite favor.

So whatever you see while touring the famous temples and mausoleums of Egypt, the Hittites came out marginally ahead. Both sides came out chastised into peacemaking. Wouldn’t it be nice if some of those currently engaged in self-destructive wars in this same region today came to a similar conclusion? Maybe they should read some history.

*****

A big thanks to Judith Starkson. She’ll give away a paperback copy of Hand of Fire to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Judith Starkson. She’ll give away a paperback copy of Hand of Fire to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.