Welcome to my blog. The week of 1–7 July 2011, I’m participating with more than two hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom Giveaway Hop,” accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one with a Revolutionary War theme. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

Welcome to my blog. The week of 1–7 July 2011, I’m participating with more than two hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom Giveaway Hop,” accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one with a Revolutionary War theme. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

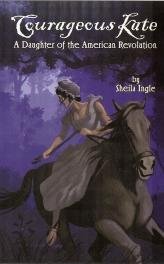

Relevant History welcomes YA author Sheila Ingle, a retired educator and teacher of writing for 37 years, and winner of the DAR Historic Preservation Award. Sheila’s interest and love for history has become a part of her new writing career. She has published articles in Sandlapper and the Greenville Magazine on the Citadel Class of ‘44 and the Frank Lloyd Wright home in Greenville, S. C. Her two biographies for young readers are based on Revolutionary War heroines of South Carolina; both Kate Barry and Martha Bratton helped the militia defeat British and Tory troops in the Upcountry in two different battles. Courageous Kate and Fearless Martha also refused to reveal information about their husbands’ whereabouts to the enemy; each faced the threats with bravery and determination. Sheila’s books are available at Barnes and Noble, Amazon, and Hub City Press. For more information, check her web site and blog.

Relevant History welcomes YA author Sheila Ingle, a retired educator and teacher of writing for 37 years, and winner of the DAR Historic Preservation Award. Sheila’s interest and love for history has become a part of her new writing career. She has published articles in Sandlapper and the Greenville Magazine on the Citadel Class of ‘44 and the Frank Lloyd Wright home in Greenville, S. C. Her two biographies for young readers are based on Revolutionary War heroines of South Carolina; both Kate Barry and Martha Bratton helped the militia defeat British and Tory troops in the Upcountry in two different battles. Courageous Kate and Fearless Martha also refused to reveal information about their husbands’ whereabouts to the enemy; each faced the threats with bravery and determination. Sheila’s books are available at Barnes and Noble, Amazon, and Hub City Press. For more information, check her web site and blog.

*****

In my book, Courageous Kate, A Daughter of the American Revolution, there is a chapter called “The Art of Housewifery.” Not all of the chores that were part of these times are described, but a good many are. In my second book, Fearless Martha, a Daughter of the American Revolution, there are more descriptions of the ways eighteenth-century women ran their homes. Mothers taught their daughters at an early age how to keep a household running smoothly. The chores were endless, and many hands were needed to make light work.

In my book, Courageous Kate, A Daughter of the American Revolution, there is a chapter called “The Art of Housewifery.” Not all of the chores that were part of these times are described, but a good many are. In my second book, Fearless Martha, a Daughter of the American Revolution, there are more descriptions of the ways eighteenth-century women ran their homes. Mothers taught their daughters at an early age how to keep a household running smoothly. The chores were endless, and many hands were needed to make light work.

The Revolutionary War women that lived on the small farms were busy from before daylight to after dark. Maybe that is where the saying “a woman’s work is never done” originated. The farmer’s wife saw to the dairy, the chickens, the vegetable and herb gardens, and cleaned house. She cured and preserved meats, made soap and candles, dried vegetables, spun thread to make cloth for clothes from her own flax, prepared meals, and doctored her family.

As I was learning about this myriad of daily tasks, I visited Middleton Gardens in Charleston, South Carolina. A large millstone was there to entertain visitors. The pole in the middle of the two stones was stout, and the stones were at least a yard wide. Turning the pole crushed the corn kernels, and this was no easy task. My whole body was involved in turning the pole; I quickly remembered the motions of the dance, the Twist, from years ago. I have to admit my practice at this didn’t last long, and my husband was kind enough not to laugh.

My grandparents owned a dairy farm in Kentucky, and I was always fascinated with the milking process, though I didn’t have a lot of personal luck. I admit I was leery of the cows after getting swatted by several of their tails at different times. There was no choice during the eighteenth century for this task, because milk was used for drinking, making butter, and cooking. Also, the cows had to be milked every day because they produced up to five gallons of milk daily. Churning is an easy, but tiring process. It sometimes took almost an hour of plunging that dasher up and down in the churn to turn that creamy milk into butter. (My husband and I have butter molds from both sides of our families that we treasure.)

When I taught kindergarten, we made candles at Christmas. It seemed an endless task for my eighteen students to walk around the table dipping their string into the hot wax. I went to Michael’s to buy the wax, but that was not available two hundred years ago. In the colonial days, the hard fat of cows or sheep was melted for the wax or perhaps beeswax was used. Bayberries were often added to give off a pleasant scent when burning, but almost a bushel of berries was needed to make just a few candles. Believe it or not, many women could make as many as 200 candles in one day. I did read that mice liked to eat candles, so the housewives had to store them carefully.

I enjoy using my crock pot to make stews or soups. The smells after several hours of cooking are an encouragement that supper is in process. In those earlier times, a large, iron pot filled with meat and vegetables would also cook all day in the fireplace. The chickens would have come from the yard, or the deer meat from a hunting expedition. The vegetables were from the kitchen garden and any herbs from the herb garden. The wife took care of scalding and plucking the feathers of the chicken. She would have prepared the ground, planted the seeds, weeded and watered the garden, and then picked her vegetables and herbs. Sometimes the family would eat on this stew for several days, with daily additions. Everything took a lot of time. Nothing was wasted. This old rhyme describes how a stew might keep on cooking. “Pease porridge hot. Pease porridge cold. Pease porridge in the pot nine days old. Some like it hot. Some like it cold. Some like it in the pot nine days old.”

John and I met Revolutionary War reenactors at Cowpens National Battlefield the other weekend, and I learned about another time-consuming task called cording. I was not familiar with this, but learned quickly that with the help of a lucet that one cord could be put together to make a stronger, square cord. These cords were used for women’s stays, drawstring bags, button loops, and anything else that needed a tie-together. A sewing basket would have cords in various stages of completion. (There are several internet sites available to find more information about this task, as well this YouTube video to help you learn this craft.) From the little bit of experience I have had with holding the yarn and the lucet, expertise making this necessity would take practice.

Speaking of the reenactors, they have learned to share this time period with us with much proficiency. They are always willing to share their knowledge and know-how of these times and the tasks that both men and women needed for survival. It is a worthwhile drive to visit any of their many campsites at Revolutionary War events, and I encourage you to do so. From the food they cook to the tents they set up, they will help open your eyes to an ordinary day in the lives of our early American families.

These are a few comparisons of housewifery between the eighteenth century and the twenty-first century; there are many others. With the well-being of their families hanging in the balance, these strong and courageous women did their jobs of taking care of both hearth and home. They left us a legacy of the importance of seeing to our households, and it is one to remember and follow their models.

*****

A big thanks to Sheila Ingle. She’ll give away a print copy of Courageous Kate to someone who contributes a legitimate comment on this post today or tomorrow. I’ll choose one winner from among those who comment by Thursday 7 July at 6 p.m. ET, then post the name of the winner on my blog the week of 11 July. Delivery is available within the U.S. only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.