Welcome to my blog! The week of 2 July – 9 July, I’m participating with more than one hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom to Read” giveaway hop, accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs listed in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one focused on some facet of the American War of Independence. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

Welcome to my blog! The week of 2 July – 9 July, I’m participating with more than one hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom to Read” giveaway hop, accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs listed in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one focused on some facet of the American War of Independence. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

Relevant History welcomes Helena Finnegan, a native of Boston, the city where her love and appreciation for liberty, the sacrifices of those who fought for it, and the revolution began. The 1976 Bicentennial, complete with tall ships and fervent Patriots and British soldiers on historic grounds and waters solidified her commitment to promoting, preserving, and sharing this era. She’s written nationally and internationally and is an educator, researcher, and writer of 18th-century topics. Her work appeared in Patriots of the American Revolution and Journal of the Early Americas magazines and Allthingsliberty.com. She’s working on a historical fiction novel set in 1781. For more information, check her web site, and look for her on Twitter and Pinterest.

Relevant History welcomes Helena Finnegan, a native of Boston, the city where her love and appreciation for liberty, the sacrifices of those who fought for it, and the revolution began. The 1976 Bicentennial, complete with tall ships and fervent Patriots and British soldiers on historic grounds and waters solidified her commitment to promoting, preserving, and sharing this era. She’s written nationally and internationally and is an educator, researcher, and writer of 18th-century topics. Her work appeared in Patriots of the American Revolution and Journal of the Early Americas magazines and Allthingsliberty.com. She’s working on a historical fiction novel set in 1781. For more information, check her web site, and look for her on Twitter and Pinterest.

*****

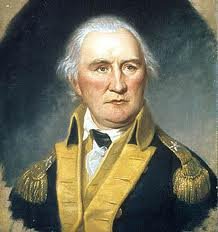

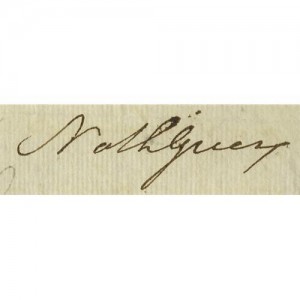

He was what would be called today “the complete package.” Strong-willed, determined, respected, self-educated, loyal, and a gifted leader. He’s known as the unsung hero of the American Revolution who helped save the war, though few today recognize his name or deeds beyond monuments or places on the map.

He was what would be called today “the complete package.” Strong-willed, determined, respected, self-educated, loyal, and a gifted leader. He’s known as the unsung hero of the American Revolution who helped save the war, though few today recognize his name or deeds beyond monuments or places on the map.

Yet if it were scripted by Hollywood, New Englander General Nathanael Greene could be an 18th-century action figure. A handsome, flawed, but kind and dependable hero loyal to his Commander-in-Chief and the Glorious Cause. He rose above his disability and learned from his mistakes to become a trusted and sought-after commander capable of seeing the big picture, willing to take risks and do what was necessary to succeed. So it was no surprise when General Washington gave him the two most difficult assignments in the War for Independence: that of Quartermaster General during which he saved the ill-fed and under-equipped army with food, supplies, and forage for animals, and that of commander of the Southern Army where he rebuilt a decimated army and expelled the British from the south. However, his eight-year journey from 1775 to 1783 as Washington’s close friend and most trusted, longest-serving general and eventual hero wasn’t without great obstacles and sacrifices.

“We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again.”

In the winter of 1780, after assuming command of West Point, General Greene was exhausted, ill, and broke having used his health and money to train, equip, supply, and lead soldiers since 1775. Only his courage, faith, determination and unwavering belief kept him going. It was these qualities that General Washington had come to rely upon and turn to, giving him the second most important command of the war, that of commander of the Southern Army.

Six long years after the conflict had begun, Americans’ spirits plunged lower than the value of the Continental dollar. Military defeats, perennial supply struggles, and lack of currency and military pay added to a seemingly endless war.

Months after the crushing defeat of American forces at Camden, South Carolina, when General Horatio Gates fled north and left the remains of militia and army to reconstitute themselves, the army awaited its new, southern commander. It was against this backdrop that Greene took on what must have felt like an impossible task. After six years of various commands, success as Quartermaster General, lobbying Congress, losing battles, and taking backseats to other leaders, this appointment was monumental. Unwritten and unspoken were the words of his Excellency: save the southern theater and thus, the War for Independence. Washington knew that if there was anyone capable of such a feat, it was General Nathanael Greene.

Months after the crushing defeat of American forces at Camden, South Carolina, when General Horatio Gates fled north and left the remains of militia and army to reconstitute themselves, the army awaited its new, southern commander. It was against this backdrop that Greene took on what must have felt like an impossible task. After six years of various commands, success as Quartermaster General, lobbying Congress, losing battles, and taking backseats to other leaders, this appointment was monumental. Unwritten and unspoken were the words of his Excellency: save the southern theater and thus, the War for Independence. Washington knew that if there was anyone capable of such a feat, it was General Nathanael Greene.

No stranger to hardship and challenges, General Greene was well-prepared for what lay ahead of him in the southern colonies, where Britain was on the verge of winning the war. His famous quote, “We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again,” displayed his ambition and unflagging commitment.

Self-taught, officer material

A self-taught military man, Washington’s “fighting Quaker” was a gifted strategist, advisor, and natural leader. He possessed brilliant organizational skills that he used to save lives as Quartermaster General during the iconic winter encampments at Valley Forge and Morristown.

Greene faced many hurdles to prove that a partially disabled Quaker and an inexperienced soldier could not only fight, but lead men in the coming conflict. Despite prejudice from his fellow Rhode Island Kentish Guards, who felt a lame soldier was not “officer material,” he was promoted to Brigadier General in the Rhode Island state army. General Washington then appointed Greene to the same rank in the Continental Army. In him, Washington must have seen something of himself: a well-read, self-educated, passionate man whose loyalty and ability to comprehend the long-term nature of the conflict made him dependable. Later, despite the terrible losses of Forts Washington and Lee, General Washington didn’t give up on Greene. While Greene sought to restore his reputation, Washington knew Greene would learn from the terrible decision to defend unsalvageable forts and lose men, just as he learned from his errors during the French and Indian War.

Following his two years as Quartermaster General, Greene resigned the post but kept his field command, returning to campaigns. Though some battles were lost or a draw, he inflicted damage to British forces, gained experience, and learned how to prepare his troops. His greatest challenge came in the southern theater, where all his experiences, military studies, training, and skills were brought together. Entering into the melee after the Americans’ success at the Battle of King’s Mountain, Greene developed a bold strategy. He united his forces with General Daniel Morgan and made the incredible decision to divide his small army in half to delay British engagement, employ guerilla tactics, and gather more soldiers. Working with Morgan, who led Cornwallis away from his supply lines and on a chase through North Carolina, allowed Greene time to re-build and re-equip his men. Understanding the critical need for supplies and preparation, he ordered all boats secured to transport his troops across the Dan River ahead of the British. In what became famous as “the Race to the Dan,” the Americans escaped capture by a few hours and lived to fight on, re-grouping in Virginia, while Cornwallis’s obsession with destroying Greene had exhausted his men and depleted his supplies. Greene later used the boats to slip his troops back across the Dan, chase the British, and engage them in future battles. The southern tide literally turned for the Americans, thanks to General Nathanael Greene, who successfully routed the British from the south, north to Yorktown, Virginia, where they were hemmed in and forced to surrender in October 1781.

Following his two years as Quartermaster General, Greene resigned the post but kept his field command, returning to campaigns. Though some battles were lost or a draw, he inflicted damage to British forces, gained experience, and learned how to prepare his troops. His greatest challenge came in the southern theater, where all his experiences, military studies, training, and skills were brought together. Entering into the melee after the Americans’ success at the Battle of King’s Mountain, Greene developed a bold strategy. He united his forces with General Daniel Morgan and made the incredible decision to divide his small army in half to delay British engagement, employ guerilla tactics, and gather more soldiers. Working with Morgan, who led Cornwallis away from his supply lines and on a chase through North Carolina, allowed Greene time to re-build and re-equip his men. Understanding the critical need for supplies and preparation, he ordered all boats secured to transport his troops across the Dan River ahead of the British. In what became famous as “the Race to the Dan,” the Americans escaped capture by a few hours and lived to fight on, re-grouping in Virginia, while Cornwallis’s obsession with destroying Greene had exhausted his men and depleted his supplies. Greene later used the boats to slip his troops back across the Dan, chase the British, and engage them in future battles. The southern tide literally turned for the Americans, thanks to General Nathanael Greene, who successfully routed the British from the south, north to Yorktown, Virginia, where they were hemmed in and forced to surrender in October 1781.

In less than a year, Washington’s “fighting Quaker” had successfully pulled off a miracle. General Greene’s story is made all the more poignant because it is true. He was an underdog whose determination, confidence, vision, skills and abilities were recognized by someone who gave him the chance to succeed—and ultimately created the opportunity for America to begin.

*****

A big thanks to Helena Finnegan. She’ll give away a $5 Amazon gift certificate to someone who contributes a legitimate comment on this post today or tomorrow. Make sure you include your email address. I’ll choose one winner from among those who comment on this post by Friday 4 July at 6 p.m. ET, then publish the name of all drawing winners on my blog the week of 14 July. And anyone who comments on this post by the 4 July deadline will also be entered in a drawing to win a copy of one of my five books, the winner’s choice of title and format (trade paperback or ebook).

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.