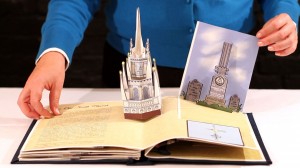

Relevant History welcomes Denise D. Price, creator of The Freedom Trail Pop-Up Book. Having seen twenty countries on five continents, Denise has a certified case of wanderlust. Inspiring a love of history, architecture, and world culture, her travels have been a major influence on how she views the world, reacts, interacts, designs and breathes. Denise was introduced to the paper arts over twenty years ago at a summer arts intensive. Her passion for the paper was stoked and has burned ever since. Holding an MBA in International Business, she combines her astuteness for business and her eye for detail to create marketable and interesting art. For more information, check her web site, and look for her on Facebook and Twitter.

Relevant History welcomes Denise D. Price, creator of The Freedom Trail Pop-Up Book. Having seen twenty countries on five continents, Denise has a certified case of wanderlust. Inspiring a love of history, architecture, and world culture, her travels have been a major influence on how she views the world, reacts, interacts, designs and breathes. Denise was introduced to the paper arts over twenty years ago at a summer arts intensive. Her passion for the paper was stoked and has burned ever since. Holding an MBA in International Business, she combines her astuteness for business and her eye for detail to create marketable and interesting art. For more information, check her web site, and look for her on Facebook and Twitter.

*****

Established in 1951, The Freedom Trail® is a 2.5-mile footpath running through Boston, Massachusetts. The trail highlights sixteen nationally significant historic sites that tell the story of Boston’s role in the American Revolution. It includes sites like Old North Church (ever famous for hosting the two lanterns that spurred Paul Revere on his midnight ride), Bunker Hill Monument, Granary Burying Ground (where you’ll find such illustrious figures as Samuel Adams and the five victims the Boston Massacre), and Faneuil Hall. The trail, demarcated by a red trail line (sometimes painted and sometimes inlaid in brick on walkways), now attracts more than four million visitors annually.

It originated in 1951, a tumultuous time in the United States. The Korean War was ongoing, McCarthyism was emerging, and racial tensions were riding high. In Boston, the idea for The Freedom Trail was born as a way to preserve and promote the part of our history that is most unifying, our fight for liberty and justice. Through a series of charged newspaper columns, illustrious journalist Bill Scofield proposed organizing the numerous landmarks as a way to keep Boston tied to its patriotic past.

After reading the columns and finding subsequent public support for the project, then-mayor John Hynes took on the task of creating the footpath. Though many of the sixteen official historical sites located on The Freedom Trail had been operating as independent museums for decades, Mayor Hynes put together a committee of concerned citizens, business people, and other city leaders to create the network that became the official trail.

By 1954, The Freedom Trail (rejected names included Puritan Path and Liberty Loop) had more than 40,000 annual visitors. The telltale red path line appeared in 1958.

The Freedom Trail as Inspiration

In 2010 I was one of the millions of Freedom Trail visitors. It was clear to me that there is no other place in the United States where you can take in the rich history of America’s Revolution than in Boston. I was captivated. I wanted something special to take home and share with family in Denver. I needed to share with them the beauty of the trail.

In 2010 I was one of the millions of Freedom Trail visitors. It was clear to me that there is no other place in the United States where you can take in the rich history of America’s Revolution than in Boston. I was captivated. I wanted something special to take home and share with family in Denver. I needed to share with them the beauty of the trail.

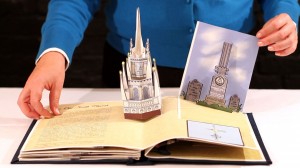

I began searching for a pop-up book. For years pop up books have been my souvenir of choice. More than a t-shirt or a mug that simply says, “I’ve been to this place,” a pop-up book is a way to share and relive the experience after the fact. They capture architecture, art, history, and culture in a way that no other printed material can, 3-D! They are educational as well as sentimental and fun to share with family and friends.

But I never did find such a book on my trip, and I left Boston disappointed. However, I didn’t give up my quest. Through extensive online research I found there were no pop-up books about Boston’s historic sites except Fenway Park. When I moved to neighboring Cambridge, MA later that year, I decided to create one. And what better way to share the city than to share the story of The Freedom Trail?

Making History Pop Off the Page

The research phase of the book was extensive. I spent hours at each site examining architectural detail, talking to staff, volunteer guides, and other trail scholars about minute details of the buildings, restoration efforts, and hidden spaces within each site. Some of my favorite discoveries were the views of The Common atop Park Street Church, the mechanical workings of the historic clock on the Old South Meeting House, the one-ton Paul Revere Bell of King’s Chapel, and the crypt at Old North Church.

The research phase of the book was extensive. I spent hours at each site examining architectural detail, talking to staff, volunteer guides, and other trail scholars about minute details of the buildings, restoration efforts, and hidden spaces within each site. Some of my favorite discoveries were the views of The Common atop Park Street Church, the mechanical workings of the historic clock on the Old South Meeting House, the one-ton Paul Revere Bell of King’s Chapel, and the crypt at Old North Church.

After the research was done, the paper-engineering and illustrating began. With notes, photos, and a love of the trail to guide me, I began the painstaking work of cutting, folding, pasting, drawing, and writing. The finished book includes sixteen architecturally and historically accurate pop-ups as well as hand-drawn illustrations and a succinct written history of the trail and its landmarks. In 2013, after three years of work, editing, fixing, and paper-cuts, the book was finished. I’m working now, to self-publish and produce a limited run of 5,000 books. I hope they’ll be used in homes, libraries, classrooms, and book collections from coast to coast. A portion of the proceeds will be donated to The Freedom Trail Scholars Program, a non-profit dedicated to bringing interactive history education into greater-Boston area classrooms.

The book is now available for pre-order ($45) on Kickstarter.com, where you’ll find more information on the book and fantastic Freedom Trail rewards, including private and behind the scenes tours. If I am funded, I will be able to obtain the final color dummy book from the assembly house. After any edits are completed, the book will go to press. Once printed, the book will be hand-assembled, piece-by-piece, and glued together. When the inside is complete, it will be mounted into the hard cover binding, boxed and shipped to Boston, where, with the help of The Freedom Trail® Foundation, The Freedom Trail® Pop Up book will be available to the public.

The book is now available for pre-order ($45) on Kickstarter.com, where you’ll find more information on the book and fantastic Freedom Trail rewards, including private and behind the scenes tours. If I am funded, I will be able to obtain the final color dummy book from the assembly house. After any edits are completed, the book will go to press. Once printed, the book will be hand-assembled, piece-by-piece, and glued together. When the inside is complete, it will be mounted into the hard cover binding, boxed and shipped to Boston, where, with the help of The Freedom Trail® Foundation, The Freedom Trail® Pop Up book will be available to the public.

*****

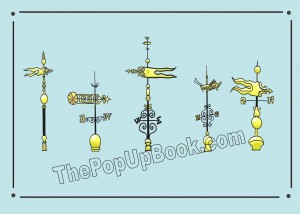

A big thanks to Denise Price. She has created a limited-edition set of note cards featuring original illustrations of the five historic Freedom Trail weather vanes (shown with watermark), and she’ll give away a set of these note cards to three people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery for the cards is available within the United States only.

A big thanks to Denise Price. She has created a limited-edition set of note cards featuring original illustrations of the five historic Freedom Trail weather vanes (shown with watermark), and she’ll give away a set of these note cards to three people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery for the cards is available within the United States only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

For ten years, an execution hid murder. Then Michael Stoddard came to town.

For ten years, an execution hid murder. Then Michael Stoddard came to town.