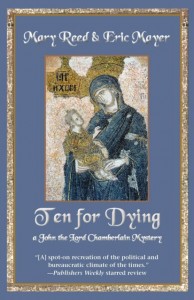

Relevant History welcomes back Mary Reed. She and Eric Mayer contributed several stories to mystery anthologies and Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine prior to 1999’s One For Sorrow, the first novel about their protagonist John, Lord Chamberlain to Emperor Justinian I. Ten for Dying, the latest entry in a series Booklist Magazine named as one of its “Four Best Little Known Series,” will be published in March 2014 by Poisoned Pen Press. Find out more about the authors on their web site.

*****

As Two for Joy opens, our protagonist Lord Chamberlain John sees a remarkable sight during a thunderstorm in Constantinople: a stylite, one of those holy men who spend their lives perched atop a column, bursts into flames.

Argument about the cause of spontaneous human combustion has raged in scientific publications and the public prints for at least the past couple of centuries. In Familiar Letters On Chemistry, In its Relations To Physiology, Dietetics, Agriculture, Commerce, and Political Economy (1861), Justus Liebig observed with some irritation that a cause not understood is used to explain an occurrence also not understood, the theory being disease causes accumulation of combustible gas in cellular tissue which “when kindled by an external cause, by a flame, or by the electric spark, effects the combustion of the body.”

Another “electric spark” theory was earlier advanced by F. J. A. Strubel in an 1848 work, The Spontaneous Combustion of the Human Body, With Especial Reference to its Medico-legal Significance, which speculates if electricity is accumulated in the body and subsequently discharged, spontaneous combustion may occur.

J. G. Millingen’s Curiosities of Medical Experience (1839) covers several of the better known cases, among them a priest whereby circumstances “…would seem to warrant the conclusion that the electric fluid was the chief agent in the combustion.” Millingen mentions hydrogen gas, which one expert notes can develop in those who suffer certain diseases, with combustion resulting from a uniting of hydrogen and electricity, presumably meaning static electricity as sometimes occurs when we disrobe.

Tipplers beware!

A remarkable letter to the editor from one A. Booth of Colchester in the September 15, 1832 issue of The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction links drinking to spontaneous combustion via witchcraft.

Citing the 1744 case of Grace Pitt, an Ipswich fishmonger’s wife, Booth states Grace was said to be a witch, adding it was well-known witchcraft could only destroy certain parts of bodies and some members could be protected against such spells. That Grace’s hands and feet were not consumed when she caught fire was attributed by country people to just such a spell—did he mean dueling witches were involved? He further opines old ladies said to be witches were so-called from “…their excessive devotion to spirituous liquors, which…[in every case has] been found to predispose to spontaneous combustion…”

An unsigned article on Temperance and Teetotal Societies in the April 1853 issue of Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine relates John Anderson, a carrier, was found burnt to death in a roadside field. He was last seen in an extremely intoxicated state smoking a pipe. It is conjectured a spark from his pipe ignited alcohol fumes from his drinking and thus combustion occurred.

A letter in the October 6, 1832 issue of the same magazine from W.A.R. of St Pancras, London, argues calling such cases spontaneous is incorrect, mentioning Pierre Aimee Laire’s Essay on Human Consumption from the Abuse of Spirituous Liquors, which states such cases occur when an imbibing individual’s breath came into contact with a flame. W.A.R’s theory is since Grace enjoyed an evening pipe and having lately consumed spirits, while lighting her pipe her breath caught fire and set fire to her spirit impregnated body.

The connection between death by burning and drinking, leading to carelessness with lamps and so forth, is so obvious it’s hardly worth mentioning, but what about someone known to eschew all spirituous liquors? The insinuation given is the victim was probably a secret tippler.

Used as defense in murder trial

In possibly the most inventive pleading heard in a criminal case, spontaneous combustion was advanced as causing the death of a countess in June 1847. A household servant eventually confessed to strangling her when discovered stealing her jewels, surrounding her with inflammable material, and setting it alight. Convicted of robbery, murder, and arson, he later obtained a free pardon—on condition he emigrated to America, according to Sabine Baring-Gould’s Historic Oddities and Strange Events (1889).

An anonymous article in the April 1861 issue of Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine points out actual evidence of the phenomenon was not known because all cases occurred when the person was alone and therefore nobody could know what had happened. However, attempts to explain the phenomenon continue.

The debate continues

In 2012 Professor Brian J. Ford of Cambridge University suggested acetone as a feasible cause of spontaneous combustion. It seems under some conditions such as diabetes, alcoholism, certain diets, or teething, the body creates the highly inflammable substance. He reports acetone-soaked pork tissue was used to make scale models of humans that were dressed and set alight, being reduced to ashes within thirty minutes.

Another explanation was advanced by Dr Matthew Ponting of the University of Liverpool in a TV documentary last year. He investigated Tutankhamun’s mummification, and it appears those carrying out the process did not follow the correct procedure or else made a mistake. Examination of the pharaoh’s skin under a scanning electron microscope showed carbonization, thought to be the result of a combination of oxygen, the linen used in the process, and embalming oils. As a result, he said, Tutankhamun’s body appears to have “cooked” soon after it was mummified.

Moving from science and crime to spontaneous human combustion as a plot device, the best known instance is the fiery death of the tippler Krook, collector of rags, papers, etc., as described in Dickens’ Bleak House. Given our stylite was unlikely to be drinking spirituous liquors, we provided a different explanation for his terrible death in keeping with the limitations of the era.

Moving from science and crime to spontaneous human combustion as a plot device, the best known instance is the fiery death of the tippler Krook, collector of rags, papers, etc., as described in Dickens’ Bleak House. Given our stylite was unlikely to be drinking spirituous liquors, we provided a different explanation for his terrible death in keeping with the limitations of the era.

*****

A big thanks to Mary Reed. She’ll give away a .pdf copy of Ten for Dying to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET.

A big thanks to Mary Reed. She’ll give away a .pdf copy of Ten for Dying to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.