Relevant History welcomes back Susanne Alleyn. The Executioner’s Heir, about Charles Sanson’s youth and early career, is Susanne’s latest novel. She is the author of the Aristide Ravel series of historical mysteries set in 1780s/90s Paris, in which some of the Sansons make guest appearances. She is currently working on a fifth Ravel novel, on the sequel to The Executioner’s Heir, and on a heavily annotated edition of A Tale of Two Cities. For more information, check out her web site.

Relevant History welcomes back Susanne Alleyn. The Executioner’s Heir, about Charles Sanson’s youth and early career, is Susanne’s latest novel. She is the author of the Aristide Ravel series of historical mysteries set in 1780s/90s Paris, in which some of the Sansons make guest appearances. She is currently working on a fifth Ravel novel, on the sequel to The Executioner’s Heir, and on a heavily annotated edition of A Tale of Two Cities. For more information, check out her web site.

*****

Throughout history, people have regarded the public executioner much as they regarded the undertaker. The undertaker’s job has always had an “ick” factor attached, originating from a superstitious dread of human corpses and people who dealt with them. But the person who, in a formal judicial process, deliberately transformed a living person into a corpse was far worse.

So who would willingly choose to become an executioner, and choose to remain in the job?

While writing The Executioner’s Heir, the first of two novels about eighteenth-century Parisian executioner Charles-Henri Sanson, I came across the autobiography of Albert Pierrepoint, the most famous British executioner of the 20th century. Pierrepoint’s attitude toward his “craft” uncannily matched the psychological makeup and motivations that I had already constructed, from my historical research, for my fictional portrayal of Charles Sanson.

Becoming a Hangman

There were, naturally, many surface differences between the two. Pierrepoint (1905-1992), like most British hangmen, came from a blue-collar background; “official executioner” was a part-time occupation, returning only a modest flat fee per engagement. Both his father and uncle were hangmen and young Albert evidently decided to follow in their footsteps because such a useful civil servant received a remarkable amount of respect from his neighbors.

Charles-Henri Sanson (1739-1806), on the other hand, was a fourth-generation executioner in a wealthy family that—like many others—passed its lucrative title down from father to son and considered itself practically aristocratic. In pre-revolutionary France, the master executioner of Paris was a high-ranking court officer, received a generous salary, and enjoyed a great deal of prestige among colleagues from lesser towns.

Notwithstanding the Sanson family’s pretensions to semi-nobility, most of the superstitious public still viewed the executioner and his household as the vilest and least desirable neighbors possible. The master executioner and his aides were responsible for all forms of public punishment, from shaming by exposure on the pillory to whipping and branding, from relatively humane hanging to the cruelest and most long-drawn-out forms of execution like breaking, burning, or quartering. For centuries throughout Europe, executioner’s sons had inevitably had to become executioners themselves because no one else would ever think of giving them a job, or even of socializing with them. Since the Middle Ages, the executioner’s touch had been considered unclean, contaminated by death, torture, and contact with corpses, and only the most broad-minded or desperate would choose to mingle with him.

“A Gentle, Friendly, Kindly Man”

Despite the public revulsion toward the Sansons and their occupation, the few surviving contemporary accounts of Charles Sanson suggest that, aside from the official duties he was obliged to carry out, he was a remarkably decent, conscientious, and compassionate human being. Well educated, he had studied anatomy and medicine—not to improve torture techniques, but, like his father and grandfather before him, in order to maintain a sort of free clinic in which, when not at work, he doctored the poor who were willing to endure contact with the executioner in order to get the treatment they couldn’t afford elsewhere. “His profession aside,” an acquaintance whom Sanson had cured of a mysterious illness wrote about him, “he was a gentle, friendly, kindly man.”

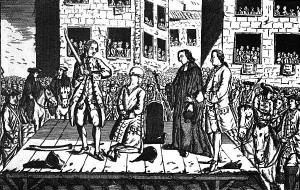

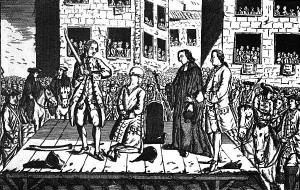

Execution by sword of the comte de Lally, May 9, 1766. Although probably not illustrated by an eyewitness, it does show the executioner as a young man (Sanson was 27 at the time).

Execution by sword of the comte de Lally, May 9, 1766. Although probably not illustrated by an eyewitness, it does show the executioner as a young man (Sanson was 27 at the time).

The greatest irony of a life full of ironies was that, after three decades of officiating at often horrific punishments under the absolute monarchy, Sanson became the most famous public executioner of the French Revolution. The Revolution, of course, soon abolished such cruel traditional execution methods as breaking on the wheel and replaced them with the democratic, reliable, and humane guillotine. This and other legal reforms must have greatly relieved Sanson for a time—until the political cataclysm of the Terror obliged him to execute more people with the guillotine than he had ever had to hang, break, or behead by sword in all his career before the Revolution. During 1793 and 1794, the “gentle, friendly, kindly man” would be ordered to behead his king and queen, a few minor royals, many prominent revolutionaries, and several of his own former bosses in the Parisian law courts, among about three thousand people convicted of various crimes, both heinous and petty, under the severe emergency laws of the Terror.

So how did such a man keep his sanity, and justify his part in not only the savage cruelty of the pre-revolutionary legal system but also in the sheer number of executions of the Terror in Paris, and in the frequent injustices that took place both before and during the Revolution? How could Sanson bring himself to put someone to death when he strongly suspected that that person had not deserved such a punishment?

Christopher Lee as a middle-aged Charles Sanson in La Révolution Française (1989). Sanson was described as tall, strong, and good-looking in the family history published by his grandson Clément, but no contemporary portrait exists of him.

Christopher Lee as a middle-aged Charles Sanson in La Révolution Française (1989). Sanson was described as tall, strong, and good-looking in the family history published by his grandson Clément, but no contemporary portrait exists of him.

The swelling number of death sentences in Paris during the last weeks of the Terror appalled him. Guillotining a record fifty-four people in one day, including an eighteen-year-old servant girl who, he stated, looked about fourteen, drove him to a four-day mental breakdown. “I do not glorify myself with a sensitivity that cannot be mine,” Sanson wrote in his diary soon afterward; “I have seen the suffering and death of my fellow men too often and too closely to be moved easily. If what I feel is not pity, it must be the result of a malady of my nerves; perhaps it is the hand of God punishing me for my cowardly obedience to that which so little resembles the justice I was born to serve? I do not know; but for some time now, every day, when the hour [to collect condemned prisoners] comes, a vertigo seizes me that holds me in its grip and cruelly tortures me . . . I feel a redoubling of the fever that night and day devours me; it is like fire flowing under my skin.”

Why, in the midst of the carnage in 1794, consumed by guilt, didn’t Charles-Henri Sanson simply quit his job and honorably retire, as he did do a year later, well after the Terror had ended?

*****

Join us here tomorrow for the conclusion of Susanne Alleyn’s post. She’ll give away three electronic copies of The Executioner’s Heir to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Saturday at 6 p.m. ET.

Join us here tomorrow for the conclusion of Susanne Alleyn’s post. She’ll give away three electronic copies of The Executioner’s Heir to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Saturday at 6 p.m. ET.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

In contrast, when bourgeois men joined an army, their women shouldered the burden of maintaining the family farm or business. To keep from starving, they might work in excess of twelve hours a day—which helps explain why we have comparatively few letters and journals from them. If these women followed their menfolk into the army—whether the men were soldiers or civilian contractors—the women risked privation. When food was scarce, they might be forced to serve in the hospital, or cook, or launder or mend soldiers’ clothing for miniscule wages. They birthed their babies in tents. They slept in the cold with their men.

In contrast, when bourgeois men joined an army, their women shouldered the burden of maintaining the family farm or business. To keep from starving, they might work in excess of twelve hours a day—which helps explain why we have comparatively few letters and journals from them. If these women followed their menfolk into the army—whether the men were soldiers or civilian contractors—the women risked privation. When food was scarce, they might be forced to serve in the hospital, or cook, or launder or mend soldiers’ clothing for miniscule wages. They birthed their babies in tents. They slept in the cold with their men.