Relevant History welcomes Susan Higginbotham, a prize-winning author who has published historical fiction and biography. Her latest historical novel, Hanging Mary, her first to be set in the United States, is narrated by Mary Surratt and her young boarder, Nora Fitzpatrick. To learn more about Susan and her books, visit her web site and blog, and follow her on Facebook.

Relevant History welcomes Susan Higginbotham, a prize-winning author who has published historical fiction and biography. Her latest historical novel, Hanging Mary, her first to be set in the United States, is narrated by Mary Surratt and her young boarder, Nora Fitzpatrick. To learn more about Susan and her books, visit her web site and blog, and follow her on Facebook.

*****

One of the shadier characters—literally—to frequent Mary Surratt’s Washington, D.C., boardinghouse in the spring of 1865 was a mysterious young woman named Sarah Slater, who kept her comely face hidden under a veil.

Confederate Courier

Born in 1843 in Middletown, Connecticut, to parents of French extraction, Sarah Antoinette Gilbert, known also as “Nettie,” grew up in that state. In the late 1850’s, however, most of the family moved to eastern North Carolina, where in June 1861, Sarah married Rowan Slater, who had been working in New Bern as a dancing master. Rowan enlisted in the Confederate army, as did three of Sarah’s brothers. One brother died in Goldsboro, apparently of illness, and the other two grew disillusioned with army life and eventually deserted.

Meanwhile, Sarah, childless and deprived of her husband’s company, decided in January 1865 to return to New York, where her mother was living. Confederate officers granted her a pass to cross through the Confederate lines. Someone, however, realized that Sarah, with her fluent French acquired from her parents, would be an excellent choice to convey messages between Richmond and Montreal, where the Confederacy had an outpost. If caught, she could always claim that she was a native of Canada. Why she agreed to this proposal we cannot know. Perhaps Sarah wanted to do her part for the cause in which her husband was serving; perhaps she was simply adventurous and bored.

Sarah’s first assignment was to carry papers to Montreal, a task she accomplished in February 1865. Mary Surratt’s son John, another courier, met Sarah in New York and traveled with her to Washington, D.C., where yet another Confederate operative, Augustus Howell, met Sarah in front of Mary Surratt’s boardinghouse and took her to Virginia.

In March, Sarah once again made the hazardous trip North, this time staying overnight at the Surratt boardinghouse, much to the interest of Mary’s boarder Louis Weichmann, who gave up his bedroom for the veiled lady. General Edwin Gray Lee, a Confederate agent based in Montreal, wrote on 22 March that he had “helped . . . to get the messenger off. I pray she may go safely.” On 25 March, Sarah arrived once again at the Surratt boardinghouse. This time, Mary and John Surratt traveled with her to Maryland, where they were met by the distressing news that Howell, who had been assigned to take Sarah across the Potomac and then to Richmond, had been arrested. John Surratt took it upon himself to take Sarah to Richmond, where they remained until 1 April. Two days later, they arrived in Washington, to be greeted with the news that Richmond had fallen to the Union. The next morning, 4 April, they went North again. It was Sarah’s last mission for the Confederacy.

In March, Sarah once again made the hazardous trip North, this time staying overnight at the Surratt boardinghouse, much to the interest of Mary’s boarder Louis Weichmann, who gave up his bedroom for the veiled lady. General Edwin Gray Lee, a Confederate agent based in Montreal, wrote on 22 March that he had “helped . . . to get the messenger off. I pray she may go safely.” On 25 March, Sarah arrived once again at the Surratt boardinghouse. This time, Mary and John Surratt traveled with her to Maryland, where they were met by the distressing news that Howell, who had been assigned to take Sarah across the Potomac and then to Richmond, had been arrested. John Surratt took it upon himself to take Sarah to Richmond, where they remained until 1 April. Two days later, they arrived in Washington, to be greeted with the news that Richmond had fallen to the Union. The next morning, 4 April, they went North again. It was Sarah’s last mission for the Confederacy.

New York Matron

John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Lincoln on 14 April 1865, a crime that sent Mary Surratt and three others to the gallows in July 1865. In the investigation and trials that followed the assassination (John Surratt was tried in 1867 but went free), the name of the lady known only as “Mrs. Slater” or by her aliases of “Kate Thompson” or “Kate Brown,” came up frequently, but no one seemed to know her whereabouts. One defendant, George Atzerodt, who had been assigned to kill Vice President Johnson but lost his nerve, claimed in one of his confessions that Sarah “knew all about the affair.” He described her as “about 20 yrs of age, good looking & well dressed. Black hair & eyes, round face.” In another confession, he added, “Mrs. Slater went with Booth a great deal.”

Nonetheless, the government failed to locate Mrs. Slater. This was left to the Hartford Evening Press and the Hartford Courant, which with help from their readers identified her as the former Sarah Gilbert of Middletown and Hartford; in the latter city, the Courant sniffed, she had “enjoyed a doubtful reputation.” But no one followed up on this information, and it was not until 1984 that James O. Hall, noted for his research into the Lincoln assassination, traced Sarah’s history from childhood through April 1865. Even then, it was left for later researchers to find her history past that date.

In fact, Sarah had made little effort to hide. She and her husband, Rowan Slater, reunited in New York City after the war, but their marriage would not last. In August 1866, Sarah took what was then the extraordinary step of seeking a divorce, alleging that Rowan had been unfaithful to her. The divorce was granted in November 1866, apparently because Rowan did not contest the allegations. He returned to North Carolina, but Sarah stayed in New York. On 5 December 1867, she married for a second time. Her husband, twenty years her senior and with a number of children, was Jacob M. Long, the superintendent of the Harlem Gas Light Company and also an alderman associated with the Tammany Hall political machine. The marriage produced no surviving children.

Jacob Long died in 1889. By 1902, Sarah was living in Poughkeepsie, New York, and working as a nurse. Then, in 1912, Sarah’s sister Laura Louise Spencer died in Brooklyn, leaving a widower, William White Spencer, a police department clerk. A year later, on 22 July 1913, Sarah, the former Confederate courier, married her brother-in-law William, who had served in the Union army. The couple moved to Manhattan.

The marriage was short-lived. William died in October 1914. Sarah eventually returned to Poughkeepsie, where she died of chronic parenchymatous nephritis on 20 June 1920, leaving behind land in several states, numerous articles of jewelry, and a collection of souvenir spoons. Like many ladies of her time, she felt no need to be candid about her age; as a result, her tombstone shaves a dozen years off her date of birth. Perhaps it also helped to conceal an exciting past about which, as far as we know, the old lady who died in Poughkeepsie had been completely silent.

*****

A big thanks to Susan Higginbotham. She’ll give away a paperback copy of Hanging Mary to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Susan Higginbotham. She’ll give away a paperback copy of Hanging Mary to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Relevant History welcomes Regency romance author Maria Grace, who has her PhD in Educational Psychology and is a sixteen-year veteran of the university classroom, where she taught courses in human growth and development, learning, test development and counseling. None of which have anything to do with her undergraduate studies in economics/sociology/managerial studies/behavior sciences. She blogs at

Relevant History welcomes Regency romance author Maria Grace, who has her PhD in Educational Psychology and is a sixteen-year veteran of the university classroom, where she taught courses in human growth and development, learning, test development and counseling. None of which have anything to do with her undergraduate studies in economics/sociology/managerial studies/behavior sciences. She blogs at  A couple eloping to Grenta Green is a fairly common plot device for romances set in the early 1800s. But why was it done (other than because it sounds really romantic), and what cheaper, easier alternatives were at hand for a couple inclined to elope?

A couple eloping to Grenta Green is a fairly common plot device for romances set in the early 1800s. But why was it done (other than because it sounds really romantic), and what cheaper, easier alternatives were at hand for a couple inclined to elope? Gretna Green is three hundred twenty miles from London, the largest British population center of the early 1800s. My local highways boast an 80 or 85 mile-per-hour speed limit, so I can travel that distance in half a day, no bother. In the early 1800s those speeds were unheard of. Most people walked. Everywhere. Only the very wealthy had horses and carriages of their own.

Gretna Green is three hundred twenty miles from London, the largest British population center of the early 1800s. My local highways boast an 80 or 85 mile-per-hour speed limit, so I can travel that distance in half a day, no bother. In the early 1800s those speeds were unheard of. Most people walked. Everywhere. Only the very wealthy had horses and carriages of their own. A big thanks to Maria Grace. She’ll give away an ebook copy of The Trouble to Check Her to two people who contribute comments on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET.

A big thanks to Maria Grace. She’ll give away an ebook copy of The Trouble to Check Her to two people who contribute comments on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Relevant History welcomes P.A. De Voe, an anthropologist, Asian specialist, and incorrigible magpie for collecting seemingly irrelevant information. Her first published mystery, A Tangled Yarn, is a contemporary cozy. In her current writing, however, she has jumped back in time and place, immersing her stories in the Ming Dynasty. She’s published several historical short stories, From Judge Lu’s Ming Dynasty Case Files, in anthologies and online. Her newly published adventure/mystery YA trilogy (Hidden, Warned, and Trapped) takes place in 1380 A.D. China. To learn more about P.A. De Voe and her books and to get a free short story, visit her

Relevant History welcomes P.A. De Voe, an anthropologist, Asian specialist, and incorrigible magpie for collecting seemingly irrelevant information. Her first published mystery, A Tangled Yarn, is a contemporary cozy. In her current writing, however, she has jumped back in time and place, immersing her stories in the Ming Dynasty. She’s published several historical short stories, From Judge Lu’s Ming Dynasty Case Files, in anthologies and online. Her newly published adventure/mystery YA trilogy (Hidden, Warned, and Trapped) takes place in 1380 A.D. China. To learn more about P.A. De Voe and her books and to get a free short story, visit her  A big thanks to P.A. DeVoe. She will give away a paperback copy of Hidden to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

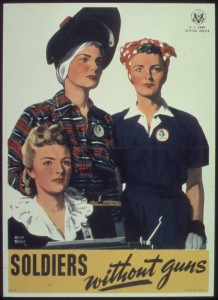

A big thanks to P.A. DeVoe. She will give away a paperback copy of Hidden to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide. Relevant History welcomes M. Ruth Myers, who received a Shamus Award from the Private Eye Writers of America for Don’t Dare a Dame, the third book in her Maggie Sullivan mystery series. The series follows a woman private investigator in Dayton, Ohio, from the end of the Great Depression through the end of WW2. Other novels by the author, in various genres, have been translated, optioned for film, and condensed for magazine publication. She earned a Bachelor of Journalism degree from the University of Missouri J-School and worked on daily papers in Wyoming, Michigan and Ohio. To learn more about Ruth and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes M. Ruth Myers, who received a Shamus Award from the Private Eye Writers of America for Don’t Dare a Dame, the third book in her Maggie Sullivan mystery series. The series follows a woman private investigator in Dayton, Ohio, from the end of the Great Depression through the end of WW2. Other novels by the author, in various genres, have been translated, optioned for film, and condensed for magazine publication. She earned a Bachelor of Journalism degree from the University of Missouri J-School and worked on daily papers in Wyoming, Michigan and Ohio. To learn more about Ruth and her books, visit her Housing was just one of the hardships faced by women whose husbands flooded into the military. If they wanted to live with their husband while he was in training, they’d find themselves sharing an apartment with another couple, or living in a lean-to, possibly with no bathtub. Nor were they always welcomed by locals. Two teachers from Missouri recall being called “low-down soldiers’ wives” and “damn Yankees” when they went to see their husbands at Ft. Knox, KY. The “rooms” they managed to find consisted of cots in the hall of rooming houses. When their husbands shipped out, women knew they wouldn’t see them again until the war ended—or they came home too badly wounded for further service. Because the military censored letters from men in uniform, the women at home didn’t even know the country where they were stationed.

Housing was just one of the hardships faced by women whose husbands flooded into the military. If they wanted to live with their husband while he was in training, they’d find themselves sharing an apartment with another couple, or living in a lean-to, possibly with no bathtub. Nor were they always welcomed by locals. Two teachers from Missouri recall being called “low-down soldiers’ wives” and “damn Yankees” when they went to see their husbands at Ft. Knox, KY. The “rooms” they managed to find consisted of cots in the hall of rooming houses. When their husbands shipped out, women knew they wouldn’t see them again until the war ended—or they came home too badly wounded for further service. Because the military censored letters from men in uniform, the women at home didn’t even know the country where they were stationed. A big thanks to M. Ruth Myers. No Game for a Dame (Maggie Sullivan #1) is available free for

A big thanks to M. Ruth Myers. No Game for a Dame (Maggie Sullivan #1) is available free for  Relevant History welcomes Susan Higginbotham, a prize-winning author who has published historical fiction and biography. Her latest historical novel, Hanging Mary, her first to be set in the United States, is narrated by Mary Surratt and her young boarder, Nora Fitzpatrick. To learn more about Susan and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes Susan Higginbotham, a prize-winning author who has published historical fiction and biography. Her latest historical novel, Hanging Mary, her first to be set in the United States, is narrated by Mary Surratt and her young boarder, Nora Fitzpatrick. To learn more about Susan and her books, visit her  In March, Sarah once again made the hazardous trip North, this time staying overnight at the Surratt boardinghouse, much to the interest of Mary’s boarder Louis Weichmann, who gave up his bedroom for the veiled lady. General Edwin Gray Lee, a Confederate agent based in Montreal, wrote on 22 March that he had “helped . . . to get the messenger off. I pray she may go safely.” On 25 March, Sarah arrived once again at the Surratt boardinghouse. This time, Mary and John Surratt traveled with her to Maryland, where they were met by the distressing news that Howell, who had been assigned to take Sarah across the Potomac and then to Richmond, had been arrested. John Surratt took it upon himself to take Sarah to Richmond, where they remained until 1 April. Two days later, they arrived in Washington, to be greeted with the news that Richmond had fallen to the Union. The next morning, 4 April, they went North again. It was Sarah’s last mission for the Confederacy.

In March, Sarah once again made the hazardous trip North, this time staying overnight at the Surratt boardinghouse, much to the interest of Mary’s boarder Louis Weichmann, who gave up his bedroom for the veiled lady. General Edwin Gray Lee, a Confederate agent based in Montreal, wrote on 22 March that he had “helped . . . to get the messenger off. I pray she may go safely.” On 25 March, Sarah arrived once again at the Surratt boardinghouse. This time, Mary and John Surratt traveled with her to Maryland, where they were met by the distressing news that Howell, who had been assigned to take Sarah across the Potomac and then to Richmond, had been arrested. John Surratt took it upon himself to take Sarah to Richmond, where they remained until 1 April. Two days later, they arrived in Washington, to be greeted with the news that Richmond had fallen to the Union. The next morning, 4 April, they went North again. It was Sarah’s last mission for the Confederacy. A big thanks to Susan Higginbotham. She’ll give away a paperback copy of Hanging Mary to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Susan Higginbotham. She’ll give away a paperback copy of Hanging Mary to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only. Relevant History welcomes former magazine editor and freelance writer Carolyn Mulford, who worked on five continents before making the transition to fiction. Thunder Beneath My Feet is her second middle grade/young adult historical novel. The Missouri Center for the Book selected the first, The Feedsack Dress, as the state’s Great Read at the 2009 National Book Festival. Show Me the Ashes, the fourth in her award-winning contemporary mystery series for adults, will be released in hardback and ebook on 16 March. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes former magazine editor and freelance writer Carolyn Mulford, who worked on five continents before making the transition to fiction. Thunder Beneath My Feet is her second middle grade/young adult historical novel. The Missouri Center for the Book selected the first, The Feedsack Dress, as the state’s Great Read at the 2009 National Book Festival. Show Me the Ashes, the fourth in her award-winning contemporary mystery series for adults, will be released in hardback and ebook on 16 March. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  A big thanks to Carolyn Mulford. She’ll give away a paperback copy of Thunder Beneath My Feet to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Carolyn Mulford. She’ll give away a paperback copy of Thunder Beneath My Feet to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.