Relevant History welcomes back award-winning author J.L. Oakley, who writes historical fiction that spans the mid-19th century to WW II with characters standing up for something in their own time and place. A UH Manoa graduate, she has always wanted to write about Hawaiians in the Pacific NW. When not writing in noisy cafes and researching history, she demonstrates 19th-century folkways at English Camp on San Juan Island. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Relevant History welcomes back award-winning author J.L. Oakley, who writes historical fiction that spans the mid-19th century to WW II with characters standing up for something in their own time and place. A UH Manoa graduate, she has always wanted to write about Hawaiians in the Pacific NW. When not writing in noisy cafes and researching history, she demonstrates 19th-century folkways at English Camp on San Juan Island. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

*****

Set between Vancouver Island, British Columbia and Washington, San Juan Island is one of the most beautiful places in the Pacific Northwest. With wide-open prairies on the southwest side, rolling valleys and forests in the interior and the northern end, and endless coves and secret harbors dotting its shores, the island is a magical place reached only by ferry or small airplane. On any given day you can spot the black and white forms of killer whales or orca as they hunt salmon and seal in Haro Strait or see eagles, dolphins, and seals in and around of the rest of archipela known as the San Juan Islands.

Before settlement by whites in the 1850s, San Juan Island was the home to the Coast Salish nation, Lummi of Bellingham, WA. The Songhees from modern day Victoria came over to fish the huge streams of salmon on their way to the Fraser River. For centuries, the peoples of the Salish Sea came ashore at South Beach to catch and smoke salmon and trade.

Then the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) arrived in Victoria on Vancouver Island in 1843. Not long after, they set up a salt station on the southern end of San Juan Island. In 1851, they claimed the island and created Belle Vue Farm up above South Beach. There the company farm ran sheep. To herd the flocks, they brought in company employees, Hawaiians or Kanakas, as they were called in the 19th century.

Readers might be surprised to learn that Hawaiians were living and working on the west coast of the United States before the Americans really set foot in the Oregon Territories, but Hawaiians first saw these shores in 1793 when George Vancouver brought some ali’i over from the Sandwich Islands. Twenty years later, Hawaiians were an integral part of the workforce for the Hudson’s Bay Company on the Columbia River in 1824. Their presence there is well documented at the Fort Vancouver National Park and Fort Langley (1827) in British Columbia.

Hawaiians on San Juan Island

A graduate of University of Hawaii Manoa, I have always wanted to write about Hawaiians in the NW. My first inkling of their presence came from a Honolulu Star article; Hawaiians were on Salt Spring Island in British Columbia. When I moved to Washington State years ago, I wanted to know more about the history of the area. At the library, I came across the annuals of the Washington State Historical Society. In its first volume (1904), I found the journals of the HBC Fort Nisqually. In several of the entries, the trader named actual workers, one spelled “Cowie.” I knew I was onto something. Cowie had to be the Hawaiian name, Kaui. I soon found out I was right. On a trip to San Juan Island several years later, I discovered the landmark, Kanaka Bay. Here Hawaiians lived with their Hawaiian and native wives in a place known as Kanaka Town. I was thrilled to know that Hawaiians were so close to my home.

A graduate of University of Hawaii Manoa, I have always wanted to write about Hawaiians in the NW. My first inkling of their presence came from a Honolulu Star article; Hawaiians were on Salt Spring Island in British Columbia. When I moved to Washington State years ago, I wanted to know more about the history of the area. At the library, I came across the annuals of the Washington State Historical Society. In its first volume (1904), I found the journals of the HBC Fort Nisqually. In several of the entries, the trader named actual workers, one spelled “Cowie.” I knew I was onto something. Cowie had to be the Hawaiian name, Kaui. I soon found out I was right. On a trip to San Juan Island several years later, I discovered the landmark, Kanaka Bay. Here Hawaiians lived with their Hawaiian and native wives in a place known as Kanaka Town. I was thrilled to know that Hawaiians were so close to my home.

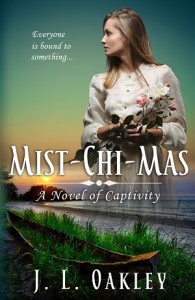

My latest historical novel, Mist-chi-mas: A Novel of Captivity, seemed like a good place to start writing about Hawaiians in the Pacific NW. To create the Hawaiian characters for Mist-chi-mas—Alani and Moki Kapuna and Kaui Kalama and his Coast Salish wife, Sally and their son Kapihi—I turned to the archives at Fort Vancouver National Park. “The Village,” an international community of HBC workers was established outside the Fort Vancouver’s walls in the late 1820s. The archives has records of the “Three Kanaka Bachelors” who lived in one of the huts. Extensive materials were also available at Fort Langley in British Columbia. At the San Juan Island National Historical Park, Kanakas performed many tasks, chiefly as shepherds. Kanakas are noted in the journals kept at Belle Vue Farm on San Juan Island:

(June) Monday 12th

Forenoon calm & clear afternoon blowing fresh from S:W: —

–an Express from Nisqually handed me by Governor Mason – Page, two Millbanks & two Kanakas.

(July) Saturday 1st

Fine clear day

Sent Nahua & all the Inds off for shells to burn for lime – oxen hauling wood for do. – killed a wedder for ration.

Leaving San Juan Island

The island and its surrounding islands were left out of the Oregon Treaty of 1846. As there was no international water boundary, both Britain and the United States claimed it. In 1859, an HBC pig from Belle Vue Farm was shot by an American settler (squatter in HBC’s eyes). This led to the infamous Pig War in 1859. Captain George E. Pickett of Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg fame was sent down from Fort Bellingham to hold American interests at the lower of the island. The Royal Navy sent over a top commander with a state of the art vessel to protect British interests. Other than the pig, no one died, and a formal agreement was made up to have both militaries jointly occupy the island until the water boundary could be decided by an international committee. They did so for twelve years. In 1872, the islands were awarded to the United States. The Royal Marines left immediately. As the Hawaiians were considered British citizens, they left as well, many returning to Victoria or Salt Spring Island in British Columbia.

The story of Kanakas is often overlooked or simply not known, but they gave much to the founding of Washington State and British Columbia. Visitors to Friday Harbor, for example, are always surprised to learn that this lively tourist destination got its name came from Peter Friday, a Kanaka shepherd whose hut was perched just above the harbor. Sailors seeking a safe, deep harbor looked for the smoke coming out of his cabin’s chimney. Friday’s Harbor, it was called then.

I hope that Mist-chi-mas will encourage readers to learn more about the Kanakas and other ethnic groups who are an integral part of Pacific Northwest history and whose contributions should be recognized and honored.

Mahsie, tillicum.

*****

A big thanks to J.L. Oakley. She’ll give away an ebook copy of Mist-chi-mas to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to J.L. Oakley. She’ll give away an ebook copy of Mist-chi-mas to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Fascinating article! My husband and I visited San Juan Island briefly a few years ago, but we didn’t discover this history. Thank you, J.L.

San Juan Island has the most wonderful history, which after going there every year for over 24 years, I’m still learning. The joint military occupation was actually peaceful with both the American Army and Royal Marines getting on quite well. We’re working on getting more interpretation out at English camp on the Kanakas. If Belle Vue Farm gets some attention, then interpretation could happen there.

A very interesting unknown bit of history.

There are a lot of places in the NW that are actually, Hawaiian. One of them if Kalama, Oregon and I think there is a falls named that.

Sounds fascinating!

I grew up near Bellingham and heard all about the pig war in school. However, we heard it as happening on Vancouver Island. I also knew about the Lummis. Actually, in our Mount Baker school district the local Indian tribe was the Nooksacks. One of the things I did in my senior typing class was retype a document about that. The Nooksacks had not sent a delegate to the federal meeting setting reservations. When that was discovered, they were told to go live with the Lummis. They refused, saying they were mortal enemies, so each family was given a plot of land. Thus, the (maybe) great grandchildren of those originals had individual homes scattered through the area, just like everybody else. They were rather Oriental looking, actually. The boy in my class had such black eyes you couldn’t tell how much of it was the pupil. My grandfather spoke the language, but I’m not sure how he learned it.

Hi, Norma, I know Mount Baker SD very well. (wrote the 3rd grade social studies curriculum for them) Many friends taught at Harmony Elementary. Nice that you looked into the tribe for your project. I know several friend who are Nooksack. The Nooksack spoke a different language from Lummi (Lummi spoke Straits Salish). They were also river people with claims on Bellingham Bay. The Lummi tribe was originally from San Juan Island and Orcas and were removed to their present location in the 1850s treaty.

Kanakas are also mentioned frequently in contemporary journals of gold rush era California. Many of them had come over as sailors, who left their ships for the mines. However the term “Kanaka” was loosely applied to anyone from the Pacific region area, not necessarily Hawaii.

Hi Steve, that’s true about all South Seas people being lumped together as Kanaka, but the word is Hawaiian. I saw several references to kanakas in the Alta California newspapers in the 1850s.