Relevant History welcomes back Anna Belfrage, who, had she been allowed to choose, would have become a time traveler. Instead, she became a financial professional with two absorbing interests: history and writing. Anna has authored the acclaimed time-slip series “The Graham Saga,” winner of multiple awards, including the HNS Indie Award 2015. Her new series, “The King’s Greatest Enemy,” is set in the 1320s and features Adam de Guirande, his wife Kit, and their adventures during Roger Mortimer’s rise to power. The third book, Under the Approaching Dark, will be released April 2017—and yes, Lincoln and its cathedral play a relevant role. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site and blog, and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Relevant History welcomes back Anna Belfrage, who, had she been allowed to choose, would have become a time traveler. Instead, she became a financial professional with two absorbing interests: history and writing. Anna has authored the acclaimed time-slip series “The Graham Saga,” winner of multiple awards, including the HNS Indie Award 2015. Her new series, “The King’s Greatest Enemy,” is set in the 1320s and features Adam de Guirande, his wife Kit, and their adventures during Roger Mortimer’s rise to power. The third book, Under the Approaching Dark, will be released April 2017—and yes, Lincoln and its cathedral play a relevant role. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site and blog, and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

*****

A bone by any other name is still a bone

No sooner do I enter a museum, but I make for the medieval exhibitions and the myriad of objects that stand testament to how present faith was in the everyday lives of our long-gone ancestors. I am especially fascinated by the reliquaries, beautifully adorned little caskets which were used to house precious relics, usually the odd bit and piece of a long-dead saint.

These relics were venerated throughout the Christian world. Some attributed healing powers to the relics, others believed the crumbling remains of an arm or a skull served to connect the penitent kneeling before it with the glory of Heaven. Initially, dismembering a saint’s remains was frowned upon, but ever-growing demand led to a more pragmatic approach. Fingers, arms, legs, were broken off from the saintly remains and carried off to a new home—in a purpose-built reliquary. The general idea was that the precious relic should be encased in gold and jewels so as to proclaim the glory of eternal life awaiting the original owner of the bones rattling round inside the casket.

In medieval times, any religious institution worth its name had to have a collection of relics. Some went quite wild and crazy in their search, bringing back everything from (yet another) purported head belonging to John the Baptist to splinters from the True Cross to phials of the Holy Blood. Trade in these items was brisk, putting it mildly, and at some point there were several heads belonging to John the Baptist doing the rounds. As to the splinters of the True Cross, should they all have been brought together, they’d have sufficed to build a new ark rather than the more modest contraption on which our Lord suffered and died.

The intrepid relic-trader soon discovered that the hunger for saintly remains was particularly strong in Carolingian Europe and England. The bones of saints were simply not enough to go around, but fortunately the catacombs of Ancient Rome were littered with old skeletons, and soon enough these old pagan bones were making their way due north, complete with whatever provenance was required to sell them as relics.

The Holy Church was irritated and embarrassed by the trade in false relics; they detracted from the value of the real thing. But in a world where people put a lot of store in owning a saintly hair or knuckle, it was difficult to shut the business down. Plus, of course, churches with relics made a lot of money from pilgrims and were therefore not all that interested in discussing the origins of the mummified hand, foot, jawbone—take your pick—they might be displaying.

No relic, no money

For a church not to have a relic was something of a minor disaster. For a medieval cathedral to lack one was unacceptable—which brings me to a little anecdote featuring Lincoln Cathedral and its lack of relics.

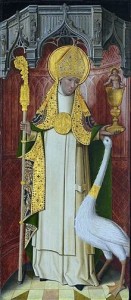

In 2016, I was fortunate enough to visit Lincoln Cathedral, and I can’t quite recall when last I was so overawed by a building as I was by this glorious, glorious church in golden stone, sitting so proudly atop its hill. The western façade is particularly eye-catching, and on one of the pinnacles that decorate it stands St Hugh of Lincoln.

In 2016, I was fortunate enough to visit Lincoln Cathedral, and I can’t quite recall when last I was so overawed by a building as I was by this glorious, glorious church in golden stone, sitting so proudly atop its hill. The western façade is particularly eye-catching, and on one of the pinnacles that decorate it stands St Hugh of Lincoln.

Long before Hugh was St Hugh, he was just plain Hugh, a bishop determined to administer his bishopric as it best served its people. He improved education, was generous to those in need, thorough in going about his duties and careful in his appointments, ensuring his diocese was as well-run as it could be—and always doing God’s work, even if it caused conflict between him and the king. By far the biggest challenge he undertook was to rebuild his minster. Lincoln Cathedral had been severely damaged by an earthquake in 1185.

Now, to rebuild a church, especially one on such a large and magnificent scale as Lincoln Cathedral, required money. One way to bring in money was to have a top-name relic to bring in pilgrims. Lincoln had none. Christ’s crown of thorns would have been a nice-to-have, but the French already had it (or one of the various crowns of thorns). Christ’s shroud would have been just as big a draw, but Turin was not about to let it go any time soon. Anything belonging to the Virgin would also have fit the bill, but alas, such relics were few and dear.

Our Hugh was probably beginning to feel a tad despondent when, in 1190, he visited France. More specifically, he was at the abbey of Fécamp in Normandy. This abbey had a fabulous treasure, an arm supposed to have belonged to no less than Mary Magdalen. A fantastic relic, one that would draw huge crowds—but the monks at Fécamp weren’t about to part with their treasure. As a consolation, Hugh was allowed to see the relic up close. It was lifted out of its reliquary, and the cloth covering the remains was folded back. Behold, the remains of a hand and arm that had once touched Christ, held him even!

Our Hugh was probably beginning to feel a tad despondent when, in 1190, he visited France. More specifically, he was at the abbey of Fécamp in Normandy. This abbey had a fabulous treasure, an arm supposed to have belonged to no less than Mary Magdalen. A fantastic relic, one that would draw huge crowds—but the monks at Fécamp weren’t about to part with their treasure. As a consolation, Hugh was allowed to see the relic up close. It was lifted out of its reliquary, and the cloth covering the remains was folded back. Behold, the remains of a hand and arm that had once touched Christ, held him even!

So overcome was Hugh (or so the story goes) that he tried to break off a piece to take home with him. The horrified monks tried to stop him, but they were no match for the determined Hugh. The arm, however, was, and no matter how he tried, Hugh could not snap off a piece. Which was when he resorted to gnawing on the relic instead, and before he had been pulled away, he had managed to dislodge two precious splinters. At last, Lincoln had a relic, however unorthodoxly acquired!

*****

A big thanks to Anna Belfrage. She’ll give away an ebook copy of In the Shadow of the Storm, first book in her “The King’s Greatest Enemy” series, to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Anna Belfrage. She’ll give away an ebook copy of In the Shadow of the Storm, first book in her “The King’s Greatest Enemy” series, to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Wonderful! I knew there were rather more heads and bits of wood than would add up but always wondered where all the ancient limbs came from, hadn’t thought of the catacombs. Love the image of the wrangling clergy and the splinters of bone. At least, I suppose, he was trying to be honest and get the real thing rather than just gnaw a sliver off his dinner. However absurd, though, I feel sorry for the skeleton, whether it was Mary’s or (more likely) not.

Thanks for visiting, Paula. I imagine the catacombs could have been a limitless source of fake relics for the black market.

I think the mummified arm was beyond caring

Ah, mummified–I did not think of that.

As a long-lapsed medievalist, I too make a beeline for the older relics in museums, particularly in Dublin (although I seem to have drifted ever earlier and am now good friends with the bog bodies there). Are you familiar with the story behind the pilgrimage church of Conques-en-Aveyron, where the monks stole the relics of Ste.-Foi in order to draw in tourists, er, pilgrims?

Hi Sheila! I’m now curious about this pilgrimage church and hope Anna responds.

Hi Sheila,

Yes, little Miss Faith (Sainte Foy is Saint Faith in English) was tortured to death in the 3rd century or so for refusing to sacrifice to the emperor. Her remains were venerated for generations in Agen (her hometown) until an intrepid monk from the abbey near Conques took it upon himself to steal them. Abbey recordds are very vague re how they got hold of little Faith, insinuating the relics sort of just popped up

But the monks took very good care of her once they got her home–gave her a nice golden reliquary. It’s easy to see why they needed an added attraction–it’s a hard place to find (I’ve been there twice–it’s a special place).

Back years ago when I was a double major in Literature and History at The University Of Texas at Dallas, I took several courses in the period. Amazing how common the theft as well as manufacture of relics was.

There’s nothing new under the sun, eh? Thanks for stopping by my blog, Kevin.

Presumably, when Hugh became a saint, then his bones became relics to be chewed up….

I shall have to follow up on that 😉 Well, actually, his remains were interred in Lincoln cathedral and generated a huge stream of pilgrims. Come the reformation, all such shrines were desecrated and the remains often ended up in a communal pit somewhere. However, legend has it that St Hugh’s remains were moved before the desecrating officers arrived, and that he was secretly interred beneath the chapter house in Lincoln.

Hugh must have been quite desperate. I’m amazed that the arm bones did not separate, for they must have been brittle by that time. I’ve not visited Lincoln Cathedral but now wish to do so.

Lincoln Cathedral qualifies as one of the most amazing structures around. Built in golden stone atop a high hill, its towers seem to be scratching the sky.

I love the imagery of the holy wrestling! Lol. I am totally intrigued by this series. Will definitely be checking them out and I LOVE this period in my fiction!

The whole time I was reading this fascinating post I was thinking about Chaucer’s odious Pardoner and his fake relics: “a sholder-boon / Of an hooly Jewes sheep” and “a mitayn” (some kind of holy mitten–whatever that is–that supposedly multiplies grain).